To Fill the Gap: A Systematic Literature Review of Group Play-Based Intervention to Address Anxiety in Young Children with Autism

Stella Wai-Wan Choy, Conor Mc Guckin, Miriam Twomey, Aoife Lynam, & Geraldine Fitzgerald

Trinity College Dublin, Ireland

Education Thinking, ISSN 2778-777X – Volume 4, Issue 1 – 2024, pp. 5–34. Date of publication: 1st March 2024.

Cite: Choy, S. W.-W., Mc Guckin, C., Twomey, M., Lynam, A., & Fitzgerald, G. (2024). To fill the gap: A systematic literature review of group play-based intervention to address anxiety in young children with autism. Education Thinking, 4(1), 5–34.

https://pub.analytrics.org/article/15/

Declaration of interests: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements: The authors gratefully acknowledge the work of Catherine O’Reilly in assisting with the inter-rater agreement in the abstract screening stage and the assistance of the two subject librarians Geraldine Fitzgerald and Greg Sheaf of Trinity College Dublin.

Authors’ notes: Stella Wai-Wan Choy is a PhD Candidate in the School of Education. She is also a Speech and Language Therapist, Play Therapist, and Counsellor. choyw@tcd.ie; Conor Mc Guckin is an Associate Professor in the School of Education. He is also an Educational Psychologist. mcguckic@tcd.ie; Miriam Twomey is an Assistant Professor in the School of Education. She is an expert in Early Intervention. twomeym6@tcd.ie; Aoife Lynam is an Assistant Professor in the School of Education. aolynam@tcd.ie; Geraldine Fitzgerald is the librarian in the School of Education. fitzgey@tcd.ie

Copyright notice: The authors of this article retain all their rights as protected by copyright laws. However, sharing and adapting this article is permitted under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution BY 4.0 International license, provided that the article’s reference (including author name(s) and Education Thinking) is cited.

Journal’s areas of research addressed by the article: 16-Early Childhood Education; 29-Guidance and Counselling; 61-Special & Inclusive Education.

Abstract

While anxiety conditions in children often manifest early in life, frequently before the age of five, and there is evidence that autism spectrum conditions (ASC) co-occur in this population, there is limited availability of interventions designed to meet the unique needs of children with both anxiety conditions and ASC. The current article examines non-pharmacological group/peer-mediated interventions for managing anxiety among children with ASC. More specifically, it focuses on the effectiveness of group play-based interventions that can alleviate anxiety in children with ASC aged 2-12 years. In doing so, this article addresses a critical gap in the existing literature and explores evidence-based strategies tailored to this specific population. Effective interventions are identified to address the needs of children of this age group. This research contributes significantly to the body of knowledge in the fields of early intervention and well-being studies.

A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)-guided comprehensive Systematic Literature Review (SLR) was conducted by searching seven prominent databases and utilising Covidence management software. The databases searched were: Academic Search Complete, ERIC, PsycInfo, Medline, Web of Science (core collection), Embase, and ProQuest Dissertations & Theses: A & I, specifically focusing on studies published in the most recent 15 years from 1996 to 2021. The review included studies concerning autistic children aged 2 to 12 years that aimed at reducing anxiety as their primary outcome. It was carried out systematically and transparently, with each step of the process clearly explained, and the rationale for the five reviewers’ choices and assumptions and decisions given.

The initial search yielded 7,300 studies, eventually narrowing down to 81 full-text articles selected for critical review. Among these, 44 proved relevant. 28 out of 35 studies that focused on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) displayed efficacy in reducing anxiety among children. Five out of eight studies centred around play-based approaches also showed effectiveness. One study employing Lego®-based therapy exhibited partial effectiveness in addressing childhood anxiety among autistic children. Among the 44 studies, four specifically centred on children aged 4 to 6 years with both anxiety and autism, and showed that group CBT effectively reduced anxiety.

This review identified nine evidence-based strategies. These, along with recommendations for future research to address anxiety in children with ASC, are analysed through the lens of an inclusive framework and early intervention theory.

Keywords

Adolescence education, Anxiety, Autism, Early childhood education, Inclusion, Play.

Anxiety is one of the most common mental health problems in children (Bitsko et al., 2022), and the comorbidity rate of autism spectrum conditions (ASC) with anxiety is high (Durand, 2015). White et al. (2009) reported signs of anxiety in approximately 50–80% of children with ASC. The co-occurrence of anxiety and ASC in children impairs their daily living skills (Drahota et al., 2011) and negatively impacts their relationships with peers, teachers, and family (Kim et al., 2000). However, as Durand (2015, p. 204) points out, “Unfortunately, for most of these disorders there is relatively little empirical evidence of effective treatment“. The current article examines non-pharmacological group/peer-mediated interventions for managing anxiety among children with ASC. More specifically, it focuses on the effectiveness of group play-based interventions that can alleviate anxiety in children with ASC aged 2–12 years. In doing so, this article addresses a critical gap in the existing literature and explores evidence-based strategies tailored to this specific population.

In this article, the terms “children with autism spectrum conditions” (ASC) and “children with anxiety conditions” have been consistently used. The rationale for choosing the term “conditions” over “disorders” is two-fold. First, this preference aligns with the social model in educational research, thus emphasizing participation in learning, rather than the medical model of disability (Retief & Letšosa, 2018). Consequently, the term “conditions” is favoured throughout the article. Second, a nuanced approach is adopted, recognizing that professionals in the autism community prefer person-centred language (e.g., children with autism spectrum conditions), while adult autism stakeholders lean towards identity-centred language (e.g., autistic people) (Taboas et al., 2023). To uphold children’s educational rights and acknowledge their developmental potential, the term “children with autism spectrum conditions” (ASC) is employed. Practical applications involve open communication, allowing language usage to align with children’s preferences.

The following research question guided this review: What are the available non-pharmacological peer-mediated play-based interventions to reduce anxiety in children aged 2-12 years with autism spectrum conditions?

This SLR had two objectives. First, it explored play-based group interventions designed for, and effective in, reducing anxiety in children with ASC. Second, it explored evidence-based strategies for this population aged 2–12 years and, in particular, for effective intervention in the age range of 4–6 years. The rationale for this age range selection is based on the early onset of anxiety conditions, before the age of five (Dalrymple et al., 2007), in addition to the scarcity of effective interventions for young children, as evidenced by recent scoping reviews (Choy et al., 2022a, 2024b), which revealed that the majority of educational and clinical interventions predominantly target children aged 7 years and above.

This research explored empirical studies that addressed anxiety in children with autism in the global context because of the abovementioned research gap (Durand, 2015; White et al., 2009). Anxiety is defined as “anticipation of future threat“ (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). No real learning occurs if a child is anxious (Goleman, 1995). Therefore, it is important to understand children’s anxiety in an educational setting. Anxiety is considered normal in response to threatening situations or stimuli. For example, if one were to encounter a fire, one might feel frightened and anxious, whereupon one would react with the “fight, flight, or freeze“ response for survival. When such a reaction becomes excessive and impairs daily functioning, one is classified as having an anxiety ‘disorder’ (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

In a meta-analysis, the worldwide prevalence of anxiety was estimated to be 6.5% among children and adolescents (Polanczyk et al., 2015), and the recent prevalence rate is on the rise, with 9.4% of children aged 3-17 years in the United States (Bitsko et al., 2022). Moreover, early onset is evident before the age of five (Dalrymple et al., 2007), with 19.6% of the patients diagnosed by the age of three (Dougherty et al., 2013). While anxiety in children is one of the most common mental health problems (Bitsko et al., 2022), research on the treatment of comorbid conditions, such as anxiety, among people with ASC is in its infancy (Durand, 2015).

This article begins by examining the rationale underpinning the systematic literature review (SLR). It scrutinizes the efficacy of peer-mediated play-based interventions targeting children concurrently experiencing anxiety and Autism Spectrum Conditions (ASC). A noteworthy aspect is the delineation of a lacuna in the extant literature pertaining to interventions tailored specifically for this demographic. Furthermore, the article deliberates upon prospective avenues for research and practice, elucidating the significance of group- and play-based interventions for children grappling with both anxiety and autism spectrum conditions.

Systematic Literature Review: The Rationale

Given the high prevalence and early onset of childhood anxiety conditions and ASC, comprehensive and transparent policies might be expected to be in place to deal with this issue. However, this is not the case, as ASC is also frequently associated with other conditions, such as anxiety, depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity, and sleep difficulties (Durand, 2015). A recent study reported that children with autism spectrum conditions (ASC) constitute 1% of the general childhood population worldwide (Zeidan et al., 2022). Simonoff et al. (2008) estimated that approximately 70% of children with ASC have another diagnostic condition. The presence of comorbid anxiety conditions can aggravate the core symptoms of ASC (Sukhodolsky et al., 2008), impair daily living skills (Drahota et al., 2011), and negatively impact relationships with peers, teachers, and family (Kim et al., 2000). For children with ASC, the co-occurrence of anxiety conditions can affect overall social functioning. For example, social anxiety may lead to avoidance of social situations, awkward interactions with peers, and further isolation from same-age peers (Myles et al., 2001).

This article addresses the comorbidity between ASC and anxiety conditions, as signs of anxiety are commonly reported in approximately 50–80% of children with ASC (White et al., 2009). More research is needed to determine which approaches are effective for children with ASC and anxiety conditions.

The Rationale for Non-Pharmacological Intervention

Examining the spectrum of treatments encompassing pharmacological, psychological, social, and behavioural modalities for children encountering anxiety conditions, Hill et al. (2016) underscored the adverse effects associated with medication. Empirical investigations have delineated an augmented propensity for behavioural activation—a therapeutic approach predicated on engaging depressed children in activities despite their reluctance—as a consequence of antidepressant medication employment in children grappling with anxiety conditions. Consequently, medication is not recommended as the primary recourse for addressing anxiety conditions in children and adolescents diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Conditions (ASC) (Hill, 2016).

Gaps in Care – The Rationale for Focusing on Children Aged 4-6 Years

While the primary objective is to review research for children aged 2–12 years, the secondary objective is to identify any available intervention that focuses on children aged 4–6 years. In addition to the rationale mentioned previously, the preschool stage, between the ages of four and six (while in Ireland, this age group is incorporated as “school-age“), presents an important opportunity for the prevention of or early intervention for anxiety conditions in children with ASC. The increase in the prevalence of mental health problems, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic, has coincided with disruptions in mental health services, leaving gaps in care for those who need it the most (Kola et al., 2022). Moreover, children begin to develop social interactions with their peers at the age of four (Scharf et al., 2016). Before that, most children play alone or notice others playing alongside, which is referred to as parallel play (Robinson et al., 2003). Preschool-aged children exhibiting a pronounced inclination towards maintaining sameness are highly likely to manifest heightened symptoms of anxiety both in their present state and during subsequent stages of middle childhood (Baribeau et al., 2020).

The limitations of previous research include the fact that only a small number of studies have examined anxiety in preschool children (Hayashida et al., 2010) or low-functioning children (Bradley et al., 2011) with ASC. Few studies have examined the risk factors or precursors of anxiety in children and the rates of subclinical anxiety symptoms in children with ASC. Niditch et al. (2012) reported that approximately 20% of preschool children (<6 years) and 9% of early elementary school children (6–9 years) with ASC had subclinical levels of anxiety. Subclinical or subthreshold symptoms are important because they reflect a potentially evolving anxiety condition or a previous anxiety condition that has partially resolved. Most children with clinically elevated anxiety symptoms aged 8 to 11 years followed a trajectory in which moderate preschool anxiety gradually increased over time (Baribeau et al., 2020). For these reasons, this age range of 4-6 years is important. Given the high and impairing rate of anxiety conditions in this ASC population, prevention studies recruiting preschool-aged or early school-aged children are needed.

Expression of Anxiety in Childhood

While not all children may demonstrate anxiety levels meeting the diagnostic criteria, comprehending the manifestations of anxiety in children is significant. The expression of anxiety conditions in children encompasses various facets: characterized by persistent worry, children with anxiety conditions often display signs of irritability or susceptibility to embarrassment. Noteworthy among childhood anxiety conditions delineated in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), are social anxiety disorder, selective mutism, and generalized anxiety disorder. Children with anxiety disorders are prone to exhibit these behaviours (Beesdo et al., 2009), such as avoidance of certain activities.

The Needs of Children with Comorbid Anxiety Conditions and ASC

Children concurrently experiencing anxiety and Autism Spectrum Conditions (ASC) require a sense of connectedness. Despite the common assumption that individuals with ASC may prefer isolation and minimal social interaction, many of them exhibit keen awareness of their social disconnection and express a desire for a different social experience (Attwood, 2004; Kasari et al., 2012). This particular demographic necessitates inclusion in group activities, opportunities for collaborative play, and implementation of a developmentally appropriate approach tailored to their needs.

This section culminates with a restatement of the research question: “What non-pharmacological peer-mediated play-based interventions are accessible for mitigating anxiety in young children aged 2-12 years with autism spectrum conditions?” Subsequently, the methodology employed in this systematic literature review (SLR) is described.

Method

A Systematic Literature Review (SLR) was conducted transparently, with each step of the process clearly explained. In each step, the rationale for the authors’ choices, assumptions, and decisions is provided. Figure 1 provides an overview of the protocol followed by the SLR method. In particular, in step two, a search strategy section provides information on the inclusion and exclusion criteria and database search. The authors describe their sources of information, search strategies, and study selection processes.

Seven prominent databases were searched. Covidence management software was used. The report was established following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework (Page et al., 2021). Figure 2 shows the PRISMA flowchart of the SLR.

The following sections will present the six steps of the systematic review process, which were adapted from Bond et al. (2016):

Step One: Clarify Aims and Objective of the SLR

Step One of the SLR involves formulating the review question and defining the secondary outcomes of interest. Task 1 aims to address the question: “What are the available effective interventions to reduce anxiety in children aged 2 to 12 with comorbid Autism Spectrum Conditions (ASC)?”. Additionally, secondary outcomes are considered, focusing on evidence-based strategies to reduce anxiety in this population. Task 2 involves identifying previous reviews addressing the same question, Task 3 entails writing the protocol, and Task 4 entails devising the search strategy.

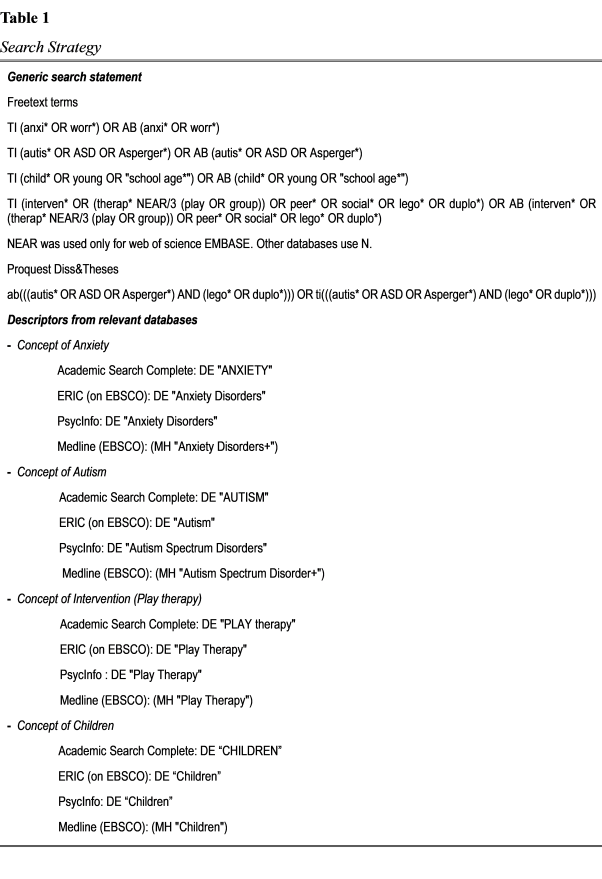

The development of the search protocol and strategy is crucial for the SLR. Key search terms, including anxiety, autism, children, intervention, play, and group, are selected to create a search strategy that is sensitive to electronic databases. The search strategy aims to ensure the retrieval of as many relevant studies as possible. Collaboration with expert librarians is essential, and a Cochrane Collaboration checklist was used to develop the search strategy.

Following a systematic approach, the research team defined text words, determined synonyms, controlled for different spellings, and identified relevant databases. Test searches were performed to assess the suitability and relevance of search strings. Steps include spelling checks, logical combinations of search terms, and syntax customization for specific databases. Validation checks were conducted to improve reliability and the final search strategies were refined based on the results. Table 1 below details the search strategy.

Step Two: Find Relevant Research

Step Two of the systematic literature review (SLR) encompassed Task 5 (Search) and Task 6 (De-duplicate and Describe Information Sources). Adhering to the PRISMA flow chart (Page et al., 2021), this phase involves the identification, screening, eligibility, and ‘included’ phase. Manual searches and searches across seven databases (Academic Search Complete, ERIC, PsycInfo, Medline, Web of Science, Embase, and ProQuest Dissertations & Theses: A & I) were conducted in April 2021. These databases cover education, social sciences, psychology, medicine, and multidisciplinary studies. The electronic search strategies, developed collaboratively by three authors and two librarians, were based on the relevant literature. The selection criteria were discussed and refined, focusing on studies published from 1996 to 2021, reflecting the most recent 15 years of research.

The review adhered to a rigorous and systematic process considering the quality of the identified data sources. Convergences and divergences in the literature were discussed, and potential research blind spots were identified. The methodology drew on frameworks such as those proposed by the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (e.g., Gough, 2007) and PRISMA (e.g., Moher et al., 2009). The methods for locating, selecting, appraising studies, and collecting/analysing data are detailed below. The search strategy was validated by two subject librarians in the medical and education fields, employing terms like “autism,” “Asperger,” “anxiety,” “worry,” “children,” “intervention,” “group,” and “play therapy” (full list in Table 1). The results for each database are presented in Table 2 within the master EndnoteX9 library.

Step Three: Appraisal

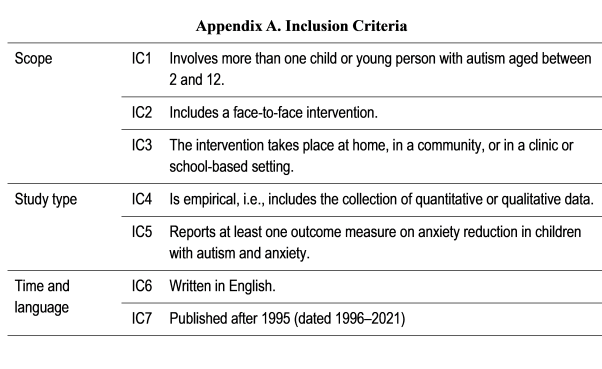

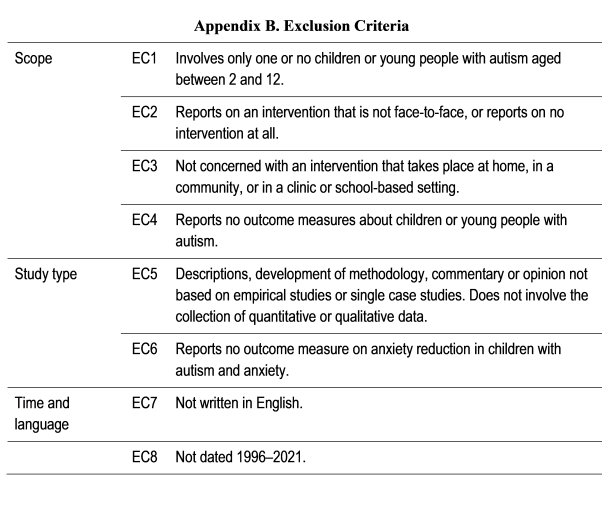

Step Three of the SLR involves Task 7 (Screen Abstracts), Task 8 (Obtain Full Text), and Task 9 (Screen Full Text). The authors collaborated with librarians to search the seven databases, input results into the master EndnoteX9 library, and transferred data to Covidence, a web-based collaboration software for systematic reviews (Covidence Systematic Review Software, www.covidence.org). The inclusion and exclusion criteria were established. The inclusion criteria are detailed in Appendix A, and only the studies that met these criteria were included. The exclusion criteria, outlined in Appendix B, guided the rejection of studies that did not meet specific requirements, such as reporting outcome measures on anxiety reduction in children with autism.

The review focused on published empirical studies and doctoral dissertations from 1996 onwards, driven by the precedent set by Bond et al.’s (2016) SLR on education interventions for children with ASD from 2008 to 2013. The scope of this review included studies involving children with autism aged 2–12 years. For instance, if a study involved participants aged 9–18 but encompassed part of the 2–12 age group (9–12), it was included. Adolescents, adults with autism, or children with anxiety-related conditions outside the autism spectrum were excluded. Studies describing interventions that did not deliver group- or play-based interventions to children with autism were also excluded. The results were confined to English-language articles published in peer-reviewed journals and doctoral dissertations.

Step Four: Assess Quality of Studies

Step Four of the SLR involves defining a method for assessing the risk of bias in the included studies and describing how the risk assessment will be utilized. However, SLRs have three limitations. First, an SLR is an evidence summary of a specific topic in the literature, emphasizing the importance of evaluating primary study quality. Second, controversies persist when interpreting the summarized results (Lau et al., 1998). Merely labelling a manuscript as an SLR does not ensure that the review was conducted or reported with due rigor (Flather et al., 1997). This review employed the Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews (ROBIS) tool, implemented in three phases, and the results are summarized in Appendix E.

Phase 1 involved assessing the relevance, engaging five reviewers, including subject librarians and researchers. Overall, there were few concerns regarding the study eligibility criteria.

Phase 2 focused on identifying concerns with the review process. The first author and an independent researcher in educational research (in a conceptually distinct area) reviewed 200 abstracts, achieving 98% inter-rater agreement. Minor issues arose for four articles owing to different understandings of the exclusion criteria. Clarification and refinement of the inclusion and exclusion criteria resolved these conflicts.

Phase 3 encompassed risk of bias assessment and bias mitigation in consultation with other reviewers and researchers.

Step Five: Synthesise Evidence

Step Five of the SLR involves outlining any planned statistical analysis, describing the intended synthesis methods for qualitative data, and detailing plans for the presentation of results following the PRISMA guidelines. Regarding the planned synthesis methods for qualitative data, ecological triangulation (Banning, 2003, p.1) was employed for data extraction and synthesis. This method involves constructing ‘ecological sentences’ structured as: “With this intervention, these outcomes occur with these population foci and within these grades (ages), with these genders… and these ethnicities in these settings.”

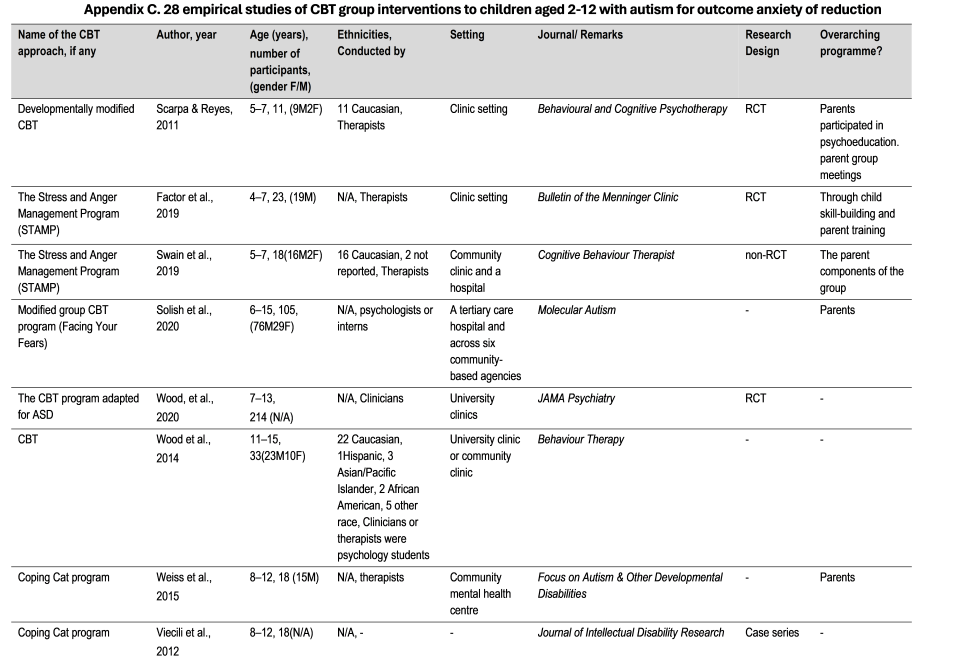

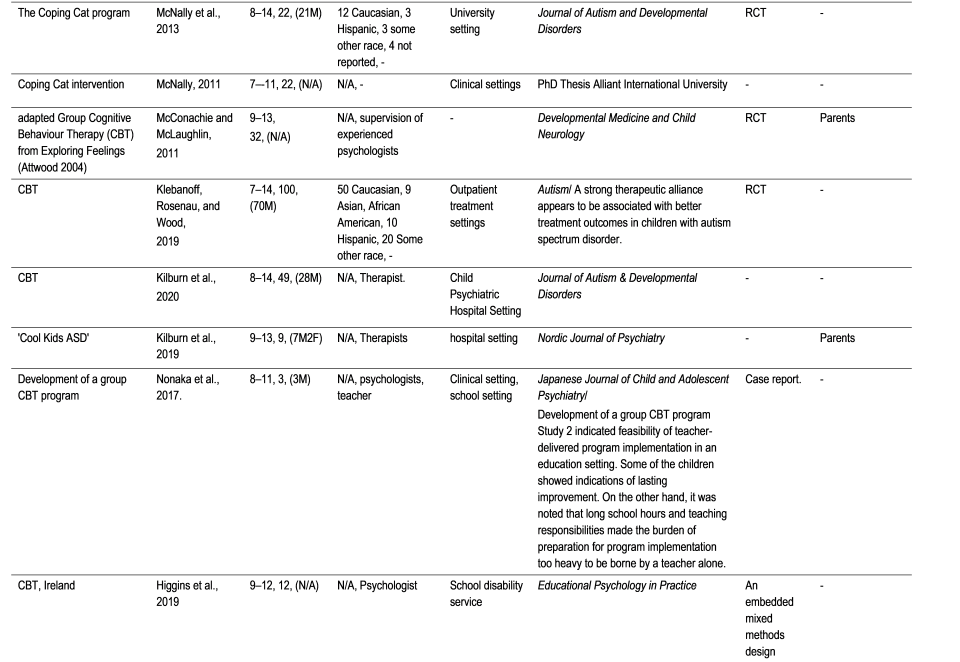

Appendices C and D follow this pattern. For Appendix C, encompassing 28 studies of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) group interventions, anxiety reduction outcomes were observed among children with co-morbid Autism Spectrum Conditions (ASC) aged 4–12 years, predominantly boys, and various ethnicities, primarily Caucasian, some Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, African American, and other racial and ethnic groups. These interventions were mainly conducted in clinical settings, with some conducted in community or school settings.

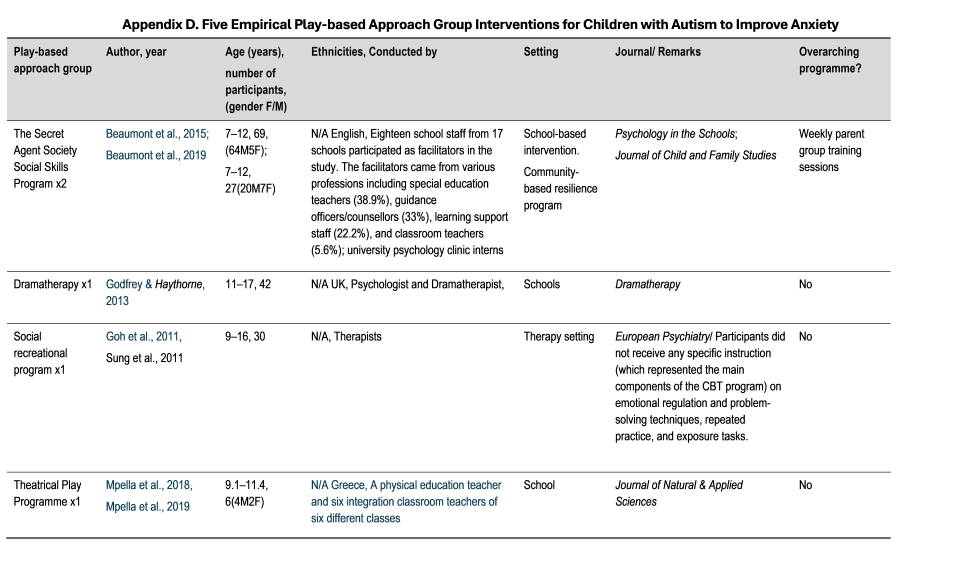

In Appendix D, which includes five studies of play-based group interventions, anxiety reduction outcomes were identified among children with comorbid ASC aged 7–12 years, mostly boys, and various ethnicities, including Caucasians, some Asian/Pacific Islanders, and other racial and ethnic groups. These interventions were primarily conducted in school settings, with one in a therapy setting.

Lastly, one study of Lego-based group intervention showed partial support for anxiety reduction outcomes, focusing on 25 children with co-morbid ASC aged 9–12 years, mostly boys (N=20), with ethnicities not reported, in a clinical setting.

Step Six: Write up and Interpret Findings

The conclusive phase of the SLR involves elucidating how information regarding the quality of evidence is applied, articulating the approach to interpreting results, and detailing the method of summarizing findings.

The PRISMA flowchart (Figure 2) provides an overview of the search process. Initially, 7300 studies were identified, which were then reduced to 81 full-text reviews. These were assessed, leading to the identification of 44 pertinent full texts—comprising 35 on Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), 8 on play-based approaches, and 1 on Lego-based therapy. The remaining 37 studies, classified as reviews or book chapters, were excluded because of duplications with the identified 44 full texts.

Results

Within the subset of CBT-focused studies, 28 out of 35 articles demonstrated effectiveness, whereas five of the eight play-based studies exhibited positive outcomes. The Lego-based therapy study demonstrated partial effectiveness. Notably, 34 of these studies offered evidence-based strategies for reducing anxiety. Four empirical studies, specifically centred on children aged 4–6 years grappling with both anxiety and autism, indicated the effectiveness of group CBT in reducing anxiety in this demographic. Table 3 below shows the results of the SLR.

CBT Studies

In analysing the 35 CBT studies, six studies were excluded because two studies were duplicates, two did not show the result or group intervention, and two were reviews.

Group Play-Based Approaches and Lego-Based Therapy

The six studies that showed effectiveness were reported in two recent scoping reviews (Choy et al., 2022a, 2024b). Their effective strategies for children aged 7-12 years will be critically reviewed later in the Discussion section for future adaptations for children aged 4-6 years.

Among the play-based studies, Goh et al. (2011) and Sung et al. (2011) suggested that group activities provided the participants with opportunities to learn and practice pro-social skills through cooperative games such as board games and treasure hunts. In their interactions with others, the participants were reminded of social etiquette, such as taking turns and playing fair.

Three other play-based studies are those by (a) Beaumont et al. (2015), conducted by school staff in a school setting; (b) Godfrey and Haythorne (2013), also conducted in school settings; and (c) Beaumont et al. (2019), using weekly tip sheets that informed school staff about the skills that children were learning, as well as how they could support them in applying these skills in the classroom and playground.

In the last play-based study, Mpella et al. (2018) reported 16 educational sessions of 45 minutes each, held over eight weeks, in a school setting. Effective strategies included cooperation with peers, role-playing and various improvisation games. The activities were conducted in a positive and fun environment.

Nguyen (2017) aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of Lego-based therapy for children and adolescents with high-functioning Autism Spectrum Conditions (HFASC), with a second aim on anxiety reduction outcomes. This author argued that social skills training may not only improve social competence but also anxiety. Nguyen experimented with a one-tailed hypothesis that children and adolescents with HFASC would make gains in symptoms of anxiety but not in any other areas of psychopathology between pre- and post-intervention. The sample included 25 high-functioning children and adolescents with autism, aged between 9 and 18 years, who were being followed up as outpatients in an outpatient mental health setting. Eight weekly 90-minute clinic-based and Lego-based therapy sessions were conducted. The study only found a significant reduction in self-reported social anxiety and parent-reported separation anxiety, but not in any of the other subscales of the Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale. This study exceeded the 12-year age limit set by the literature review. However, as it contained participants with aged 9-12 years, it was included in this literature review as explained earlier in the ‘Step Three: Appraisal’ paragraph of the method section.

In summary, these six play-based approaches were effective in reducing anxiety in children aged 7 to 12. The effective strategies included (1) group activities through cooperative games, (2) weekly tip sheets, (3) activities that took place in a very positive and fun environment, and (4) some groups conducted by school staff.

Evidence-based Strategies for Children Aged 2 to 12

This review identified nine evidence-based strategies. These, along with recommendations for future research to address anxiety in children with neurodiversity, are analysed through the lens of an inclusive framework and early intervention theory. Table 4 below summarises the evidence-based strategies to reduce anxiety in children from the 28 CBT approaches, five play-based approaches, and the Lego-based therapy, which showed effectiveness.

Evidence-based Strategies for Children Under 7 years of age

Four of the effective studies addressed group CBT for children with autism aged 4–6 years. Table 5 provides a brief description of these studies. This section of the paper will summarize the conclusions of the four studies on the issue of effectiveness and suggest future recommendations for this young population. It should be noted that although the age range of the Solish et al. (2020) study is 6-15 years, it has been included in this section because it contained children aged 4–6 years as mentioned in the ‘Step Three: Appraisal’ paragraph of the method section.

Scarpa and Reyes (2011), using a developmentally modified CBT, reported a pilot study involving participants aged 5–7 years. The study sample included 11 children with autism in a therapeutic setting. Nine weekly 90 minutes sessions were conducted. The children were divided into groups of two to four participants. The intervention focused on skill building via affective education, stress management, and understanding emotional expressions. The authors reported the results from pre- to post-treatment. All children had less parent-reported negativity/lability, better parent-reported emotion regulation, shorter outbursts, and generated more coping strategies in response to vignettes (e.g., relaxation tools). Parents also reported increases in their own confidence and in their children’s ability to deal with anger and anxiety. Evidence-based strategies included facilitating emotion regulation by teaching relaxation, and physical, social, and cognitive tools to “fix” intense emotions. Sessions were structured in such a way as to have Welcome Time, Singing, Story Time, Activity/Lesson Time, Snack, and Goodbyes, all revolving around a particular topic.

Factor et al. (2019) expanded on the pilot study by Scarpa and Reyes (2011) and conducted the Stress and Anger Management Program (STAMP) for participants aged 4–7 years. The study sample included 23 children with autism in a therapeutic setting. A total of nine weekly sessions were conducted. The structure of the nine sessions remained the same, focusing on understanding positive (e.g., happiness and relaxation) and negative emotions (e.g., anger and anxiety). This STAMP program was a developmental modification of the Exploring Feelings CBT program (Attwood, 2004), which targeted children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) aged 9–13 years (Sofronoff et al., 2005). The focus of STAMP is to teach children emotional regulation strategies, specifically what they themselves can do to manage their emotions to solve problems, reduce distress, avoid punishment or injury, and develop friendships. In addition, STAMP views parents as essential co-facilitators in helping their child to generalise self-regulation skills in contexts other than therapy groups (Hassenfeldt et al., 2015). The results demonstrated that child lability/negative affect decreased, regulation did not significantly change, and parental confidence in their child’s ability to manage anger and anxiety increased. Findings reported that negativity and lability may be particularly salient to study in younger children with ASD because they have been shown to be precursors to later emotional regulation abilities and problem behaviours (Kim-Spoon et al., 2013). Factor et al. (2019, p. 251) noted that:

“To date, STAMP appears to be the only CBT group treatment for children with ASD as young as 4 years old that may be especially relevant for treating lability/negative affect as an early component of emotional regulation capacity.“

Similarly, Swain et al. (2019) conducted The Stress and Anger Management Program (STAMP) for 18 participants aged 5–7 years. The sample included 18 children with autism in a community clinic and hospital setting. Nine weekly 60-minute sessions were conducted by clinicians. The authors concluded that the study adds to the evidence that some children with autism and no language impairment aged 5 to 7 years can benefit from a group CBT program, with a significant decrease in the levels of emotion dysregulation in terms of negative affect expression. Findings reported that two-thirds of the families who participated in the STAMP program reported a significant decrease in negative lability and/or outburst frequency, intensity, or duration. Overall, when properly implemented, STAMP can provide parents with increased confidence in their ability to manage negative affect in their children, as well as confidence in their children’s ability to use newly learned strategies to regulate their emotional outbursts. Additionally, most children experienced a reduction either in the intensity and duration or in the frequency of their outburst, although not in all three simultaneously.

Solish et al. (2020) studied a modified group CBT program (Facing Your Fears) for 105 participants aged 6 to 15 years, in a tertiary care hospital and in six community-based agencies. Fourteen weekly 90-minute sessions were conducted by clinicians in a hospital setting. The group leaders at the six community sites included 28 behavioural therapists, seven social workers, two psychologists, one psychology intern, one practicum student, two family counsellors, and one early childhood educator. Child participants and at least one parent spent time working together and apart in separate parent and child groups. Weekly home practice was assigned, and reinforcement strategies were used to encourage exposure practice between sessions.

Data were collected over six years. Hospital and community samples did not differ significantly, except in terms of age (hospital M=10.08 years; community M=10.87 years). The results indicated significant improvements in anxiety levels from baseline to post-treatment across measures, with medium effect sizes. An attempt to uncover the individual characteristics that predict the response to treatment was unsuccessful. In conclusion, this study demonstrated that community implementation of a modified group-CBT program for youth with autism is feasible and effective for treating elevated anxiety.

In summary, four studies using group CBT approaches demonstrated effectiveness in helping children aged 4 to 6 years with autism reduce their anxiety. Group, structure, concrete visual tactics, child-specific interests, teaching social and emotional tools such as negative affect expression for emotional regulation, parent involvement, home missions (skills practice tasks), and tip sheets are examples of the evidence-based strategies involved. However, all the studies were conducted in clinical or hospital settings. Swain et al. (2019) recommended expanding the group approach to the school environment or including teacher participation. Similarly, Solish et al. (2020) suggested that community settings are as feasible and effective as hospital settings.

Discussion: Summary and Future Recommendations on the Group and Play-Based Interventions for Children with Concurrent Anxiety and Autism Spectrum Conditions

This SLR provides a comprehensive summary of the methodologies employed in existing studies and offers valuable insights that can guide future research on peer-mediated interventions for children with both anxiety and autism.

The methodologies used to design the interventions in the 34 effective studies reviewed varied. For example, the duration of sessions for groups of children varied from 45 minutes (e.g., Mpella et al., 2018) to 90 minutes (e.g., Goh et al., 2011; Sung et al., 2011). The duration of the interventions ranged from eight weeks (e.g., Nguyen, 2017) to 16 weeks (e.g., Goh et al., 2011; Sung et al., 2011). The frequency of sessions ranged from once a week to twice a week (Mpella et al., 2018).

However, it is important to note that the 37 reviews and book chapters that were not included in the present review were the subject of a systematic literature review and meta-analysis by another research team (Perihan et al., 2020). These authors identified 23 studies that used CBT approaches. They categorised studies of less than 12 weeks as short-term interventions (N=8), 12 to 14 weeks as standard-term interventions (N=5), and 16 weeks or more as long-term interventions (N=10). Their results showed a moderate effect size (g=− 0.66) in reducing anxiety symptoms. Short-term interventions produced a smaller effect (g=−0.37, p<.05) than standard-term (g=−1.02, p<.05) or long-term interventions.

Regarding long-term interventions of 16 weeks or more, Fujii et al. (2013) argued that for young children with autism and comorbid anxiety, more intensive interventions, such as 32 sessions, are necessary to improve the efficacy of the intervention and skill maintenance. Longer interventions allow for additional practice of skills and extended home-school collaboration.

Given the above, a duration of 12–14 weeks will be recommended as a standard-term intervention, and 32 sessions as an intensive intervention for children with additional needs and/or anxiety risk factors.

Across the 34 studies – group-, play-, and Lego-based – included in this review that showed effectiveness in reducing anxiety, group sizes ranged from two to five children per adult group leader. For children aged 4–6 years, Scarpa and Reyes (2011) and Factor et al. (2019) included two–three children per group. Three to five children per group were included in the study by Solish et al. (2020). The group size was not specified in the study by Swain et al. (2019), but two adults were recommended for the group, one lead therapist, and one assistant. Considering the young age of the children and their additional needs, we recommend two–five children per group. If there are more than five children per group, at least one assistant is recommended on top of the trained group leader.

Inclusive Framework and Bioecological Model

Analysed from the perspectives of an inclusive framework based on the Universal Design for Learning approach (Meyer et al., 2014), early intervention theory, and the bioecological model (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2007), the evidence-based strategies that have been effective in reducing anxiety in children with comorbid autism aged 2–12 years are recommended for future research and practice.

Research on an inclusive framework, the bioecological model, and play-based approaches for early intervention has not been well-developed for this age group. Inclusion, defined as access to participation regardless of ability or disability (Meyer et al., 2014), was not stressed in the four relevant empirical studies using cognitive-behaviour therapy groups. Universal Design is a fundamental condition for inclusion (Story et al., 1998). To promote a more inclusive and diversity-embracing global community, it is imperative to establish a framework that guarantees accessibility and equal participation for individuals, regardless of their abilities. Universal Design (UD) refers to making things at all levels universal by design from the beginning. Below are the seven Principles of UD (The Centre for Excellence in Universal Design, 1997).

The authors compared the studies included in this SLR and checked whether they involved an inclusive framework. The conclusion drawn from the comparison was that most studies did not involve an inclusive framework, and the design of group interventions in future research is recommended to be universal from the outset.

The Bioecological model is defined by the fact that the relationships children have with their parents and caregivers have an impact on their development, and that these relationships are influenced by the school and community environment, which in turn is influenced by wider social, cultural, and political conditions (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2007). This model has been partly applied in limited studies involving parents (e.g., Solish et al., 2020). In this SLR, among the 34 relevant studies, only nine CBT approaches and two play-based approaches (Beaumont et al., 2015, 2019) included parent training sessions. For future research, it is essential to design interventions that involve full engagement of parents, peers, and teachers to influence children’s development.

Finally, the play-based approach, which uses play as a natural way of learning for children, has been a priority in childhood education (Gestwicki & Bertrand, 2011); however, it has not been adopted in the four relevant empirical studies (Factor et al., 2019; Scarpa & Reyes, 2011; Solish et al., 2020; Swain et al., 2019). Despite attempts to modify CBT groups for preschool children by adding stories, singing, activities, and snacks, the main and most difficult part is the teaching or lesson time.

The four studies that proved effective in reducing anxiety in children with autism aged 4 to 6 years had limitations: they were not inclusive enough, were not developmentally appropriate with play-based design, and did not take social contexts into account. To make support for children more universal and accessible in school settings, it is proposed that, in future research, school-based programmes be conducted by more trained school staff and multidisciplinary professionals. As recommended by Swain et al. (2019), extending the program to take place in the school environment or including teacher participation would be particularly helpful for children who struggle more with emotion regulation at school than at home.

Effective Strategies for Reducing Anxiety in Children

To address the research question, the nine evidence-based strategies from this SLR include parental involvement, visual cues, structure, a safe space to explore – with the cooperation of the group – activities of child-specific interests, affective education, self-regulation, strategies to regulate emotional outbursts, home missions, and a positive environment that could be adopted to explore an alternative intervention that addresses the risk factors for anxiety, that is, a combination of genetics, temperament, and environment. The evidence-based strategies reported in this SLR could be valuable resources for teachers’ curriculum planning and parental support. The future programme could be delivered by teachers and other multidisciplinary professionals, as they have the qualifications to work with children with a wide range of needs. However, as the literature often points to a lack of teacher confidence in this area (Woolf, 2022), training integrating the findings from this SLR is needed. With awareness of anxiety and evidence-based strategies, as well as training, it is conceivable that they could use this approach in school settings, that is, more universally, and make non-clinical support accessible.

Finally, modifications could be made for young children drawing from evidence-based practices for older age groups with anxiety and autism. Some evidence-based strategies identified in this SLR could also be adapted, where appropriate. For instance, interactive and activity-based group sessions, with direct practice of specific tools and strategies to reduce anxiety (i.e., emotional regulation techniques such as not expressing negative affect). Small “homework“ assignments could reinforce core concepts. Parental anxiety and parenting styles could be directly discussed in parents’ groups.

In the four group CBT studies that demonstrated effectiveness in reducing anxiety in children aged 4–6 years, effectiveness was argued using self-report and parent-report on anxiety levels. It is imperative to exercise caution when employing data triangulation, that is, self-report, parent reports, teacher reports, and group leader reports, as discrepancies in these reports are frequently noted in the literature (Burke et al., 2017). It is important to offer young children diverse self-report avenues, including visual-, audio-, and play-related means, aligned with the principles of universal design for learning. Furthermore, it is recommended that future research adopt a circumspect approach, refraining from exclusive reliance on quantitative data or standardised tests.

Conclusion

In summary, this SLR identified the prevalence and onset of anxiety in children, while highlighting a gap in practice for young children’s well-being. The expression of anxiety in children, comorbidity of anxiety and ASC in children, and rationale for group intervention followed. Particular attention was paid to peer-mediated play-based interventions for children with concurrent anxiety and ASC. Empirical research studies on an inclusive framework, bio-ecological model, and play-based approach for early intervention have not been well-developed for young children under the age of seven years to address their anxiety issues with comorbid autism. Considering that comorbidity with anxiety could be prevented through early intervention prior to adolescence, more research on this young age group is needed to understand the increase in anxiety levels from preschool to school age (Baribeau et al., 2020), and to prevent the recurrence of anxiety in the future (Ramsawh et al., 2011). Autism is frequently associated with anxiety, which increases treatment complexity. Given these findings, a developmental approach to understanding how anxiety develops, and how it may interact with the core disabilities of autism, is important.

The authors of this SLR believe that they can make a modest contribution to achieving the high-level objectives set out in Article 24 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) concerning inclusive education, to shape a sustainable society. Our ambition is to influence policy and practice concerning children’s wellbeing. Drawing on the effective strategies presented in this report, we will develop a school-based intervention to improve the understanding of anxiety and reduce anxiety in children aged 4–6 years with neurodiversity in Europe and worldwide.

References

American Psychiatric Association, DSM-5 Task Force. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™ (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.

https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Attwood, T. (2004). Cognitive behaviour therapy for children and adults with Asperger’s syndrome. Behaviour Change, 21(3), 147–161.

Banning, J. (2003). Ecological triangulation: An approach for qualitative meta-synthesis (What works for youth with disabilities project: U.S. Department of Education).

http://mycahs.colostate.edu/James.H.Banning/PDFs/Ecological%20Triangualtion.pdf [accessed 1 September 2023].

Baribeau, D. A., Vigod, S., Pullenayegum, E., Kerns, C. M., Mirenda, P., Smith, I. M., & Szatmari, P. (2020). Repetitive behavior severity as an early indicator of risk for elevated anxiety symptoms in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(7), 890–899.

Beaumont, R., Rotolone, C., & Sofronoff, K. (2015). The secret agent society social skills program for children with high‐functioning autism spectrum disorders: A comparison of two school variants. Psychology in the Schools, 52(4), 390–402.

Beaumont, R. B., Pearson, R., & Sofronoff, K. (2019). A novel intervention for child peer relationship difficulties: The Secret Agent Society. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(11), 3075–3090. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01485-7

Beesdo, K., Knappe, S., & Pine, D. S. (2009). Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 32(3), 483–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2009.06.002

Bitsko, R. H., Claussen, A. H., Lichstein, J., et al. (2022). Mental health surveillance among children — United States, 2013–2019. Mobility and Mortality Weekly Report 71(Suppl-2):1–42. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su7102a1

Bond, C., Symes, W., Hebron, J., Humphrey, N., Morewood, G., & Woods, K. (2016). Educational interventions for children with ASD: A systematic literature review 2008–2013. School Psychology International, 37(3), 303–320.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034316639638

Bradley, E., Lunsky, Y., Palucka, A., & Homitidis, S. (2011). Recognition of intellectual disabilities and autism in psychiatric inpatients diagnosed with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities, 5(6), 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/20441281111187153

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2007). The bioecological model of human development. Handbook of child psychology, 1.

Burke, M.-K., Prendeville, P., & Veale, A. (2017). An evaluation of the “FRIENDS for Life“ programme among children presenting with autism spectrum disorder. Educational Psychology in Practice, 33(4), 435–449.

https://doi-org.elib.tcd.ie/10.1080/02667363.2017.1367648

Choy, S. W.-W., Twomey, M., & Mc Guckin, C. (2022a). When a flower does not bloom: Design a school group play programme for reducing anxiety in children aged 4 to 6 years with and without – A scoping review. International Journal of Childhood Education, 3(1), 27–57. https://doi.org/10.33422/ijce.v2il.38

Choy, S. W.-W., Twomey, M., & Mc Guckin, C. (2024b). Effectiveness of peer-mediated block play for reducing anxiety in children aged 4 to 6 years with and without autism apectrum disorder. In Learning Disabilities in the 21st Century. London: Proud Pen.

Dalrymple, K. L., & Herbert, J. D. (2007). Acceptance and commitment therapy for generalized social anxiety disorder: A pilot study. Behavior Modification, 31(5), 543–568.

DOI: 10.1177/0145445507302037

Dougherty, L. R., Tolep, M. R., Bufferd, S. J., Olino, T. M., Dyson, M., Traditi, J., Rose, S., Carlson, G. A., & Klein, D. N. (2013). Preschool anxiety disorders: Comprehensive assessment of clinical, demographic, temperamental, familial, and life stress correlates. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 42(5), 577–589.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2012.759225

Drahota, A., Wood, J. J., Sze, K. M., & Van Dyke, M. (2011). Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on daily living skills in children with high-functioning autism and concurrent anxiety disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(3), 257–265.

DOI: 10.1007/s10803-010-1037-4

Durand, V. (2015). Behavioral therapies. In: S. Fatemi. (Ed.). The molecular basis of autism. Contemporary clinical neuroscience. Springer, New York, NY.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2190-4_10

Factor, R. S., Swain, D. M., Antezana, L., Muskett, A., Gatto, A. J., Radtke, S. R., & Scarpa, A. (2019). Teaching emotion regulation to children with autism spectrum disorder: Outcomes of the Stress and Anger Management Program (STAMP). Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 83(3), 235–258.

Flather, M. D., Farkouh, M. E., Pogue, J. M., & Yusuf, S. (1997). Strengths and limitations of meta-analysis: Larger studies may be more reliable. Controlled Clinical Trials, 18(6), 568–579.

Fujii, C., Renno, P., McLeod, B. D., Lin, C. E., Decker, K., Zielinski, K., & Wood, J. J. (2013). Intensive cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in school-aged children with autism: A preliminary comparison with treatment-as-usual. School Mental Health: A Multidisciplinary Research and Practice Journal, 5(1), 25–37.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-012-9090-0

Godfrey, E., & Haythorne, D. (2013). Benefits of dramatherapy for autism spectrum disorder: A qualitative analysis of feedback from parents and teachers of clients attending Roundabout dramatherapy sessions in schools. Dramatherapy, 35(1), 20–28.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02630672.2013.773131

Goh, T. J., Sung, M., Ooi, Y. P., Lam, C. M., Chua, A., Fung, D., & Pathy, P. (2011). Effects of a social recreational program for children with autism spectrum disorders-preliminary findings. European Psychiatry, 26.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-9338(11)72000-4

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam Books.

Gough, D. (2007). The Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating (EPPI) Centre, United Kingdom. Evidence in Education, 63.

Hassenfeldt, T. A., Lorenzi, J., & Scarpa, A. (2015). A review of parent training in child interventions: Applications to cognitive–behavioural therapy for children with high-functioning autism. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2(1), 79–90.

Hayashida, K., Anderson, B., Paparella, T., Freeman, S. F., & Forness, S. R. (2010). Comorbid psychiatric diagnoses in preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders. Behavioral Disorders, 35(3), 243–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/019874291003500305

Hill, C., Waite, P., & Creswell, C. (2016). Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Paediatrics and Child Health, 26(12), 548–553.

Kasari, C., Rotheram-Fuller, E., Locke, J., & Gulsrud, A. (2012). Making the connection: Randomized controlled trial of social skills at school for children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 53(4), 431–439. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02493.x

Kim, J. A., Szatmari, P., Bryson, S. E., Streiner, D. L., & Wilson, F. J. (2000). The prevalence of anxiety and mood problems among children with autism and Asperger syndrome. Autism, 4(2), 117–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361300004002002

Kim-Spoon, J., Cicchetti, D., & Rogosch, F. A. (2013). A longitudinal study of emotion regulation, emotion lability‐negativity, and internalizing symptomatology in maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Child Development, 84(2), 512–527.

DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01857.x

Kola, L., Kumar, M., Kohrt, B. A., Fatodu, T., Olayemi, B. A., & Adefolarin, A. O. (2022). Strengthening public mental health during and after the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, 399(10338), 1851-1852

Lau, J., Ioannidis, J. P., & Schmid, C. H. (1998). Summing up evidence: one answer is not always enough. The Lancet, 351(9096), 123-127.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00523-2

Meyer, A., Rose, D. H., & Gordon, D. T. (2014). Universal design for learning: Theory and practice. CAST Professional Publishing.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D.G., & The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

Mpella, M., Evaggelinou, C., Koidou, E., & Tsigilis, N. (2018). The effects of a theatrical play programme on social skills development for young children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Natural & Applied Sciences, 22(3), 828–845.

Myles, B. S., & Simpson, R. L. (2001). Effective practices for students with Asperger syndrome. Focus on Exceptional Children, 34(3), 1–14.

Nguyen, C. (2017). Sociality in autism: Building social bridges in autism spectrum conditions through LEGO® based therapy. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Hertfordshire).

Niditch, L. A., Varela, R. E., Kamps, J. L., & Hill, T. (2012). Exploring the association between cognitive functioning and anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: The role of social understanding and aggression. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 41(2), 127–137. DOI: 10.1080/15374416.2012.651994

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Aki, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLOS Medicine, 18(3), e1003583.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583

Perihan, C., Burke, M., Bowman-Perrott, L., Bicer, A., Gallup, J., Thompson, J., & Sallese, M. (2020). Effects of cognitive behavioural therapy for reducing anxiety in children with high functioning ASD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(6), 1958–1972.

Polanczyk, G. V., Salum, G. A., Sugaya, L. S., Caye, A., & Rohde, L. A. (2015). Annual research review: A meta‐analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(3), 345–365.

Ramsawh, H. J., Weisberg, R. B., Dyck, I., Stout, R., & Keller, M. B. (2011). Age of onset, clinical characteristics, and 15-year course of anxiety disorders in a prospective, longitudinal, observational study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 132(1-2), 260–264.

Retief, M., & Letšosa, R. (2018). Models of disability: A brief overview. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies, 74(1).

Robinson, C. C., Anderson, G. T., Porter, C. L., Hart, C. H., & Wouden-Miller, M. (2003). Sequential transition patterns of preschoolers’ social interactions during child-initiated play: Is parallel-aware play a bidirectional bridge to other play states?. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 18(1), 3–21.

Scarpa, A., & Reyes, N. M. (2011). Improving emotion regulation with CBT in young children with high functioning autism spectrum disorders: A pilot study. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 39(4), 495–500.

Scharf, R. J., Scharf, G. J., & Stroustrup, A. (2016). Developmental milestones. Pediatrics in Review, 37, 25– 38.

Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Charman, T., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., & Baird, G. (2008). Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(8), 921–929.

Sofronoff, K., Attwood, T., & Hinton, S. (2005). A randomised controlled trial of a CBT intervention for anxiety in children with Asperger syndrome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(11), 1152–1160.

Solish, A., Klemencic, N., Ritzema, A., Nolan, V., Pilkington, M., Anagnostou, E., & Brian, J. (2020). Effectiveness of a modified group cognitive behavioral therapy program for anxiety in children with ASD delivered in a community context. Molecular Autism, 11(1), 1–11.

Story, M. F., Mueller, J. L., & Mace, R. L. (1998). The universal design file: Designing for people of all ages and abilities. NC State University, Center for Universal Design.

Sukhodolsky, D. G., Scahill, L., Gadow, K. D., Arnold, L. E., Aman, M. G., McDougle, C. J., McCracken, J. T., Tierney, E., White, S. W., & Lecavalier, L. (2008). Parent-rated anxiety symptoms in children with pervasive developmental disorders: Frequency and association with core autism symptoms and cognitive functioning. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(1), 117–128.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10802-007-9165-9

Sung, M., Ooi, Y. P., Goh, T. J. et al. (2011). Effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy on anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 42 (6), 634–649. Available from:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10578-011-0238-1

Swain, D., Murphy, H., Hassenfeldt, T., Lorenzi, J., & Scarpa, A. (2019). Evaluating response to group CBT in young children with autism spectrum disorder. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 12, E17. DOI: 10.1017/S1754470X19000011

The Center for Excellence in Universal Design. (1997). https://universaldesign.ie/what-is-universal-design/the-7-principles [accessed 13/9/2023]

Taboas, A., Doepke, K., & Zimmerman, C. (2023). Preferences for identity-first versus person-first language in a US sample of autism stakeholders. Autism : The International Journal of Research and Practice, 27(2), 565–570.

https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613221130845

Tsafnat, G., Glasziou, P., Choong, M. K., Dunn, A., Galgani, F., & Coiera, E. (2014). Systematic review automation technologies. Systematic Reviews, 3, 1–15.

White, S. W., Oswald, D., Ollendick, T., & Scahill, L. (2009). Anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(3), 216–229. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.003

Woolf, A. (2022). Better mental health in schools: Four key principles for practice in challenging times. Taylor & Francis.

Zeidan, J., Fombonne, E., Scorah, J., Ibrahim, A., Durkin, M. S., Saxena, S., Yusuf, A., Shih, A., & Elsabbagh, M. (2022). Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Research, 15(5), 778– 790. https://doi-org.elib.tcd.ie/10.1002/aur.2696