Marginalized Youth and Their Journey to Work: A Review of the Literature

Alexandra Youmans, Benjamin Kutsyuruba, Alana Butler, Lorraine Godden, Alicia Hussain, Heather Coe-Nesbitt, Rebecca Stroud, & Christopher DeLuca

Faculty of Education, Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada

Education Thinking, ISSN 2778-777X – Volume 3, Issue 1 – 2023, pp. 61–82. Date of publication: 27 October 2023.

Cite: Youmans, A., Kutsyuruba, B., Butler, A., Godden, L., Hussain, A., Coe-Nesbitt, H., Stroud, R., & DeLuca, C. (2023). Marginalized youth and their journey to work: A review of the literature. Education Thinking, 3(1), 61–82.

https://pub.analytrics.org/article/14/

Declaration of interests: The authors declare to have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements: Funding for the systematic literature review came from the Ontario Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Development (MAESD). The views expressed in this publication are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Province of Ontario or MAESD.

Authors’ note: The authors of this article were an evaluation team for the Social Program Evaluation Group at the Faculty of Education, Queen’s University in Kingston, Canada. All authors have a doctorate in Education and are committed to improving educational opportunities and outcomes. Contact: sandy.youmans@queensu.ca

Copyright notice: The authors of this article retain all their rights as protected by copyright laws.

Journal’s areas of research addressed by the article: 1-Adolescence and Youth Development; 56-School-to-Work Transition; 19-Education Policy.

Abstract

To support the evaluation of a Canadian social program, our research team conducted a systematic literature review of marginalized youths who have experienced employment challenges. The literature review focused on the context of marginalized youth unemployment, characteristics of NEET youth (i.e., youth not in education, employment, or training), needs and barriers of NEET youth, and promising program practices for helping NEET youth with workforce transitions. The employment needs of marginalized youth were identified in relation to the barriers they face (i.e., being uninformed, underrated, uncertain, under-prepared, unaccepted, and under-resourced; Government of Canada, 2017c). To support marginalized youth in securing and maintaining employment, promising program practices must address the complex needs of this population regarding information, investment, life stabilization, skill development, guidance, and the development of networks and connections. In light of this literature review, the implications of employment program policy for NEET youths are discussed.

Keywords

Marginalized youth, NEET youth, Workplace transitions, Youth unemployment.

For the past three decades, youth unemployment has been a growing social issue in Canada and internationally (Bălan, 2014; Canada 2020, 2014; Choudhry et al., 2012; Crisp & Powell, 2017; Foster, 2017; Versnel et al., 2011). Youth unemployment is exacerbated by poor or unstable economic climates, particularly for marginalized youth (e.g., racialized immigrants, Aboriginals, individuals with disabilities, people with mental health challenges, etc.; John Howard Society of Ontario, 2014). As part of a social program evaluation, our research team conducted a literature review to better understand the ongoing problem of youth unemployment in Canada. The purpose of the literature review was two-fold: (1) to examine the employment challenges faced by marginalized youth in Canada, and (2) to explore programs developed to help marginalized youth seek and sustain employment. Marginalized youth are often referred to as at-risk (i.e., youth who are most vulnerable or at risk of disparities in access, service use, and outcomes) and NEET – young people between the ages of 15 and 29 who are not in employment, education, or training (OECD, 2017). NEET youths may find it challenging to secure long-term employment because of their low educational attainment, low motivation, poverty, homelessness, poor health, and family responsibilities. In reviewing the literature on NEET youth, we describe the current situation of marginalized Canadian youth and programs intended to support and respond to their needs. In Canada and internationally, youth in the NEET category face significant and somewhat similar difficulties in securing sustainable employment (Government of Canada, 2017c; MacDonald, 2011; Mawn et al., 2017). By examining the current challenges and program opportunities for Canadian NEET youth, we hope to provide insights into how other countries can better support their NEET populations.

Method

Using a systematic review methodology (Gough et al., 2012; Thomas & Harden, 2008), we conducted a major search of literature databases (ERIC, PsycINFO, PubMed, Queen’s Summons, and Google Scholar) with relevant inclusion/exclusion keywords determined through prior experience of undertaking literature reviews on employment-related issues for NEET populations, including the at-risk youth sub-population who fall under the NEET category (NEET-at-risk).

Relevant key search terms and number of initial publications found were identified as: youth unemployment (105,282), youth unemployment Canada (28,872), youth unemployment Ontario (8041), opportunity youth (136), NEET youth Ontario (19), NEET youth training in Canada (84), NEET youth training in Ontario (16), NEET youth +, at-risk youth (613), disengaged youth (2511), barriered youth (11), multi-barriered youth (0), NEET youth transitions into work (1840), at-risk transitions (18), at-risk youth transitions (5), NEET transitions (473), Canadian at-risk youth (8546), Ontario at-risk youth (2819), at-risk youth employment outcomes (8395), NEET employment outcomes (400), routes to employment NEET youth (1157), job matching NEET youth (53), job placement NEET youth (66), at-risk youth job matching (748), NEET youth career counselling (61), at-risk youth career counselling (1813), unemployment + work attitudes NEET youth (132), NEET youth needs (417), NEET youth barriers (152), NEET youth mentorship (35), what drives youth into NEET (93), what drives NEET youth into unemployment (787), NEET youth employment service planning (144), NEET youth and the labour market (364), and understanding NEET youth (309).

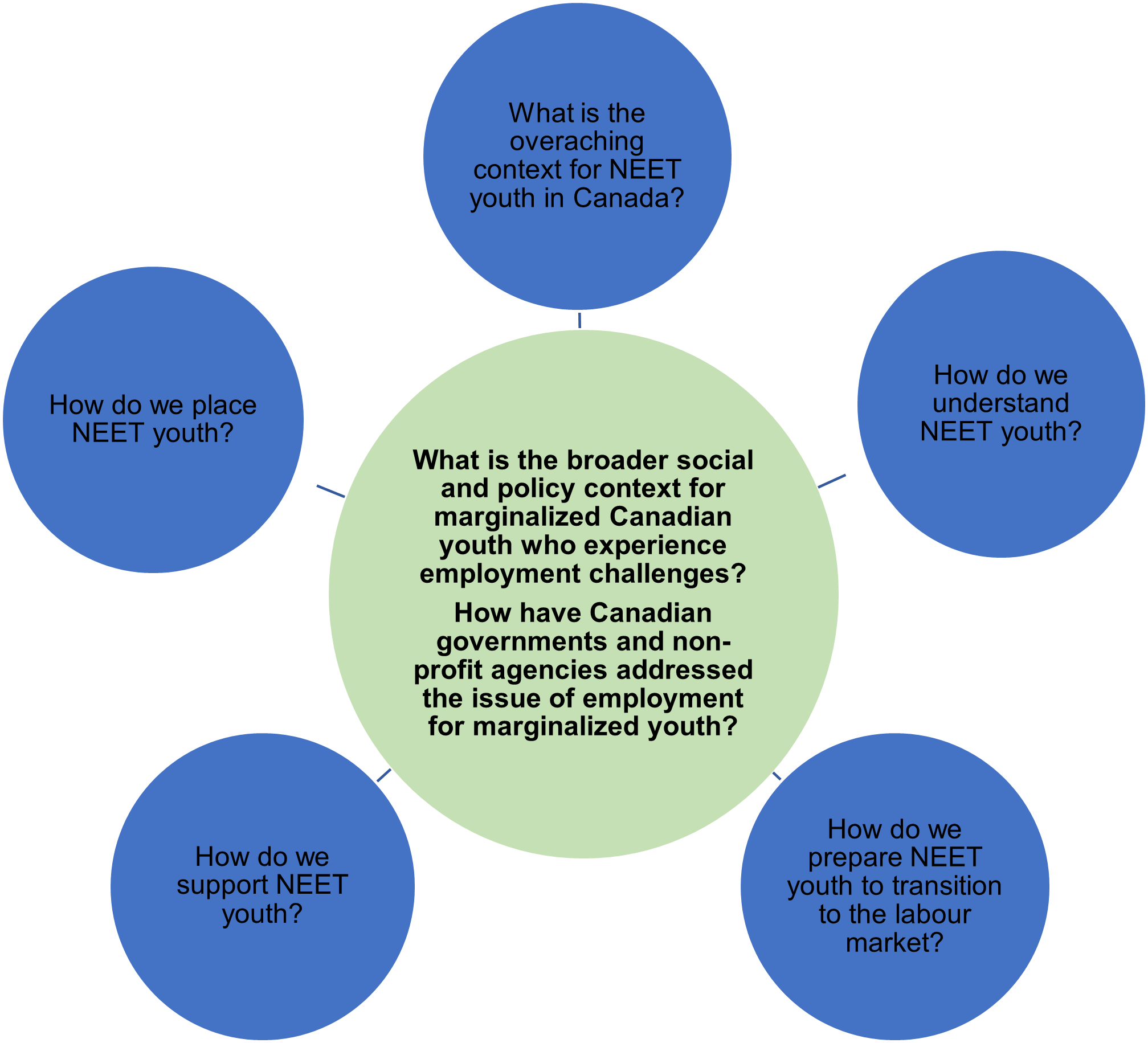

Through this search, we identified articles from recent (2000-2018) peer-reviewed published academic sources (i.e., “black literature”). Some grey literature was also included where it met our inclusion criteria, for example, government reports. The literature was analyzed for content (e.g., purpose, findings, research method, keywords) to select articles with the best-fitting evidence to answer the following two literature review questions:

To help systematize our literature search, we created a tool (see Figure 1) that illustrates sub-questions for the two overarching questions. This tool provides an overview of the systematic review and serves as a map to simplify a complex topic into more manageable components.

Figure 1

Overview Tool Used to Conduct the Systematic Review

Our initial search of the electronic databases identified 174,412 sources. Duplications were removed, reducing the total number of entries to 11,227. Our second step was to screen titles and abstracts of the citations found by electronic means against the following inclusion criteria: to have been published between 2000 and 2018; to have relevance to the research questions; to include empirical data; and for the study to be in English. A total of 10,975 were further excluded: 2324 were not focused on the study context; 6796 were not focused on our research questions; 741 were not empirical research; 126 were not in English; and 876 were outside our date parameters. Following further exclusion of reports that proved to be unobtainable (N=112), the full texts of 252 studies were retained for further screening.

The third step was to apply the same exclusion criteria to these 252 articles. Of these, 102 were selected for inclusion in this systematic review. For the full in-depth review, only those studies with keywords that focused on the five guiding questions outlined in Figure 1 were included.

In this section, we present the results of our systematic review of NEET youths. For the purposes of this paper, we report on information that is of national and international significance. The findings from the systematic review were organized according to the following seven themes:

Canadian Context of Youth Unemployment

Regardless of the state of the Canadian economy, young Canadians are more likely to be unemployed than the general population (Government of Canada, 2016). Statistics Canada recently reported that full-time employment among young people (17-24 years old, excluding full-time students) has declined significantly since the late 1970s (Statistics Canada, 2015). This is evident even among youths working full-time, as their jobs have become increasingly temporary. Although there are some positive trends in youth employment in Canada, many Canadian youth continue to experience the legacy of the 2008–09 recession, with the share of employed youth in Canada not yet returning to pre-recession levels (Government of Canada, 2016).

Youths who struggle in the labour market, including indigenous and recent immigrant youths, are more likely to be NEET. In 2015, 12.6% of Canadian youth (aged 15-29) were NEET, either seeking work or having left the workplace entirely (Government of Canada, 2016). NEET youths are at an increased risk of becoming socially isolated. Moreover, youth unemployment is associated with increased involvement in crime, mental health challenges, violence, drug use, and social exclusion (Bell & Blanchflower, 2010; Oreopoulos et al., 2006; Sonnet et al., 2010; Standing, 2011; Verick, 2009). As Bell and Blanchflower (2011) emphasized, “inaction is not a sensible option when the potential private and social costs of youth unemployment are so high” (p. 265).

Rationale for Programs that Respond to NEET

An active labour market is typically described using employment and unemployment rates as indicators. These indicators provide information about individuals who are working and individuals who are unemployed or seeking employment (Bălan, 2014). However, Bălan (2014) warns against using youth employment and unemployment rates alone to describe the labour market situation of young people, as it excludes the experiences and barriers of a growing number of young NEETs. The measurement of NEETs is a matter of concern for many countries, as the longer this population remains unemployed and out of school, the greater the risk that it will have difficulty integrating into the workforce (OECD, 2017). Given the increased complexities that NEET youth face in gaining employment compared to their non-NEET counterparts, the integration of NEET youth in Canada continues to be a major federal and provincial policy focus. For example, the Government of Canada calls for “building an inclusive society that empowers marginalized groups and individuals and supports sustainable development” (Government of Canada, 2017a). This can be achieved by “building inclusive institutions” and by “supporting voice, empowerment, and accountability through targeted policies and programs” (Government of Canada, 2017a). In addition, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Canada (2015) has made improving access to post-secondary education for indigenous populations a key imperative, with the potential to further support NEET youth.

Characteristics of NEET Youth

The NEET youth population is a heterogeneous and ever-changing group (Russell, 2013). They possess a wide spectrum of needs, based on their individual identities, life circumstances, and social contexts. Additionally, NEET youth typically face multiple barriers to entering the labour force, unlike their non-NEET youth counterparts and core-age workers. Understanding the typical characteristics of NEET youth is vital in designing policies that re-engage youth in education, employment, or training. More importantly, there is an increasing need for policymakers to consider the heterogeneous, ever-changing sub-categories of NEET youth to better design effective interventions to address their needs and the barriers they face (MacDonald, 2011).

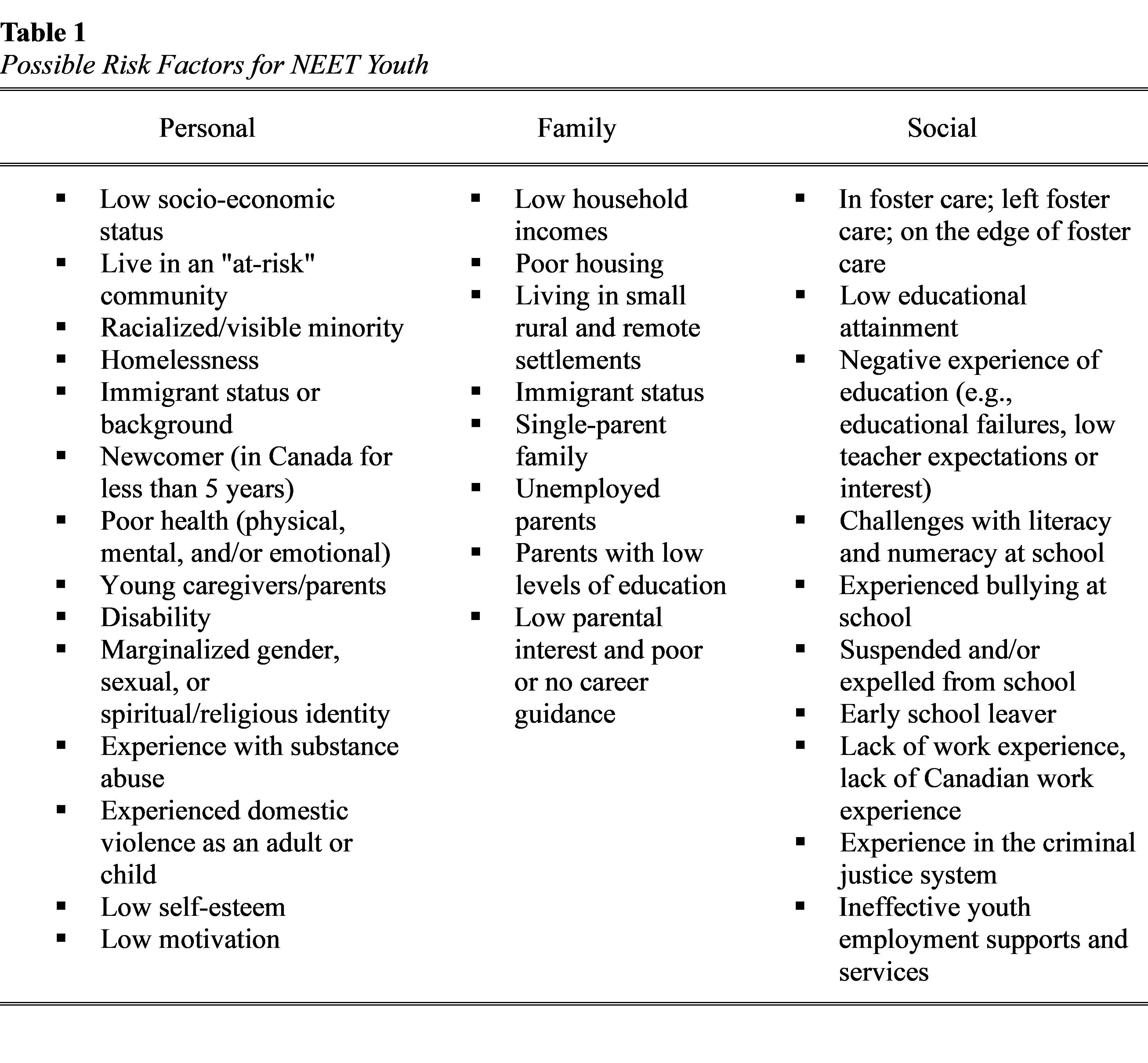

The various characteristics of NEET youth are not mutually exclusive, and it is likely that some youth experience multiple characteristics simultaneously. Moreover, NEET youths with multiple risk factors may require comprehensive support for transitioning to higher education, employment, or training. We organized the possible risk factors for NEET youth into three categories: personal, family, and social (see Table 1; Canada 2020, 2014; Government of Canada, 2017c; Inui, 2005; Marshall, 2012; Mawn et al., 2017; Mendolia & Walker, 2015; Pullman & Finnie, 2018; St. Stephen’s Community Housing and Access Alliance, 2016; Zudina, 2017).

Driving Factors for NEET Youth

Youths are driven into NEET status by numerous factors that intersect and interact with each other at various times in their lives. Some of the main driving forces include (a) economic downturns; (b) an insecure and competitive labour market; (c) discrimination in the labour market; (d) low educational attainment (more prevalent in indigenous communities); (e) lack of mentorship and support; and (f) lack of motivation or incentive to seek employment.

It has been well documented that economic downturns have had a greater impact on youth than on core-age workers (Bell & Blanchflower, 2010; Canada 2020, 2014; Galarneau et al., 2013; Inui, 2005; Marshall, 2012; Shields et al., 2006). Lightman and Gingrich (2012) argue that Canada’s depleting social welfare system has especially impacted racialized immigrants and youth who experience the lowest returns on education. Young women, individuals with low educational attainment, and those who report poor health and/or homelessness tend to be the ones who remain out of education and employment the longest (OECD, 2015). In a qualitative study of 62 NEET youths in Toronto, St. Stephen’s Community Housing and Access Alliance (2016) found that Canada’s economic downturn in the 2008-2009 period resulted in intensified job screening methods and job requirements. Consequently, youth with criminal records have been scrutinized more in the hiring process (St. Stephen’s Community Housing and Access Alliance, 2016). Furthermore, youth (especially racialized and Aboriginal youth) are overly represented in the criminal justice system across Canada, accounting for 56% of all individuals charged with crimes (McMurtry & Curling, 2008).

Insecure and Competitive Labour Market

Youth are at a greater risk of experiencing unemployment and are more likely to be laid off compared to core-age workers; this phenomenon is coined “last in, first out” (Government of Canada, 2017c, p. 6). Currently, Canadian youth are more likely to graduate from secondary school, receive post-secondary education or formal training, live at home with parents/guardians longer than in the past, begin careers later in life (in their 30s), and hold student debts (Canada 2020, 2014; Galarneau et al., 2013). Traditionally, achieving post-secondary education experience and credentials has translated into obtaining a higher income and a greater likelihood of sustainable employment. However, the reality is that Canadian youth with post-secondary credentials are more likely to be unemployed than core-age workers (6.2% versus 4.3%), and these young people are more likely than older workers to hold insecure, non-permanent jobs (Foster, 2012).

Youths are also often driven into NEET status because of the decrease in employment opportunities available to 15–20-year-olds, who experience increased competition for entry-level jobs (Canada 2020, 2014). Young people who enter the labour market in temporary/contract, part-time and non-unionised positions often feel that their employers are not committed to their career development, which does not encourage them to make a full professional commitment (Foster, 2017). This lack of employer-worker commitment continues to negatively shape young people’s early relationship with paid employment, creating what Foster called “disaffected” working relationships which can often lead to youth disengagement from the workforce.

Discrimination in the Labour Market

To fully comprehend the reasons why youth are driven into NEET status, it is imperative to think of them heterogeneously, especially if we are to gain a better understanding of why some youth struggle more than others in the labour market (Government of Canada, 2017c). Gender, racial identity, cultural identity, Aboriginal/First Nations/Metis/Inuit, Canadian-born or foreign-born, sexual orientation, spiritual/religious identity, ability, age, area of residence, and proficiency in either English or French are all factors that play a role in how youth navigate and are treated in the labour market (Canada 2020, 2014; Lightman & Gingrich, 2012; Preston, 2008; Pullman & Finnie, 2018; St. Stephen’s Community Housing and Access Alliance, 2016; Shields et al., 2006). These factors should be given adequate attention because discrimination exists in the labour market (Lightman & Gingrich, 2012; Shields et al., 2006), and it often dictates how young people fare in the labour market, pushing them to become NEETs. A less-discussed factor driving youth into NEET status is proficiency in English or French, which was evident in 2011 data illustrating that the employment rate of immigrant youth aged 15-29 was approximately 12% lower than that of Canadian-born youth (Pullman & Finnie, 2018). Moreover, “gender, visible minority status, age, and length of stay in Canada are all found to be strong predictors of economic exclusion…these social characteristics intersect in ways that result in rather profound material outcomes” (Lightman & Gingrich, 2012, p. 137). Additionally, youth with disabilities may be driven into NEET status primarily because they lack work experience and training (Pullman & Finnie, 2018).

While low educational attainment is associated with NEET-status youths (Government of Canada, 2017c; Marshall, 2012; Mawn et al., 2017; Preston, 2008; Zudina, 2017), a high level of education is associated with a higher standard of living: higher income, greater employment satisfaction, improved health, and longevity of life (Preston, 2008). Although Indigenous youth across Canada are increasingly obtaining high school diplomas, attending post-secondary institutions, and taking leadership roles in their communities, they still struggle more than their non-indigenous peers in the labour market (Government of Canada, 2017c; Pullman & Finnie, 2018). Indigenous youth still do not participate in post-secondary education to the same extent as their non-indigenous peers in Canada because of insufficient opportunities and allowances for the entry and completion of post-secondary programs (Preston, 2008). Low educational attainment can drive young Indigenous peoples living on and off reserves into NEET status; however, Indigenous youth living on reserves fare worse (Government of Canada, 2017c).

Lack of Mentorship and Support

Youths’ low self-esteem and lack of career guidance, mentorship, and support often intersect and interact with structural barriers to push them into NEET status (Foster, 2012; Mawn et al., 2017; Zudina, 2017). Parents who support and nurture their children’s post-secondary educational attainment and career aspirations play a pivotal role in preventing youth from falling into NEET status; and having educated parents often determines the family finances available to support youths’ educational and career goals (Pullman & Finnie, 2018). Pullman and Finnie (2018) explained that parents with high educational attainment significantly contributed to youths’ cultural and educational capital, which, in turn, impacted learning and skills development.

Lack of Motivation or Incentive to Seek Employment

NEET youth who are not in the labour force (NILF) for a variety of reasons (Bălan, 2014; CAMH & CMHA, 2010; Canada 2020, 2014; Government of Canada, 2017c; Marshall, 2012; Russell, 2013; Zudina, 2017) are not significantly different from the general NEET population. In a Statistics Canada report, Marshall (2012) provided an informative snapshot of the state of NILF youth in Canada: 82% of NILF youth did not want a job, while the remaining 18% (one in five) reported wanting a job but did not look for one. Similar to their NEET youth counterparts, some NEET-NILF youth have been expelled from secondary school, left school early at the secondary or primary/elementary level, are experiencing homelessness, live in an “at risk” community or a rural area with few opportunities to participate in higher education or secure employment, have family responsibilities that keep them at home, are experiencing health challenges (e.g., mental illness), or are discouraged and have given up trying to secure employment (CAMH & CMHA, 2010; Marshall, 2012; St. Stephen’s Community Housing and Access Alliance, 2016).

NEET Youths’ Barriers and Needs

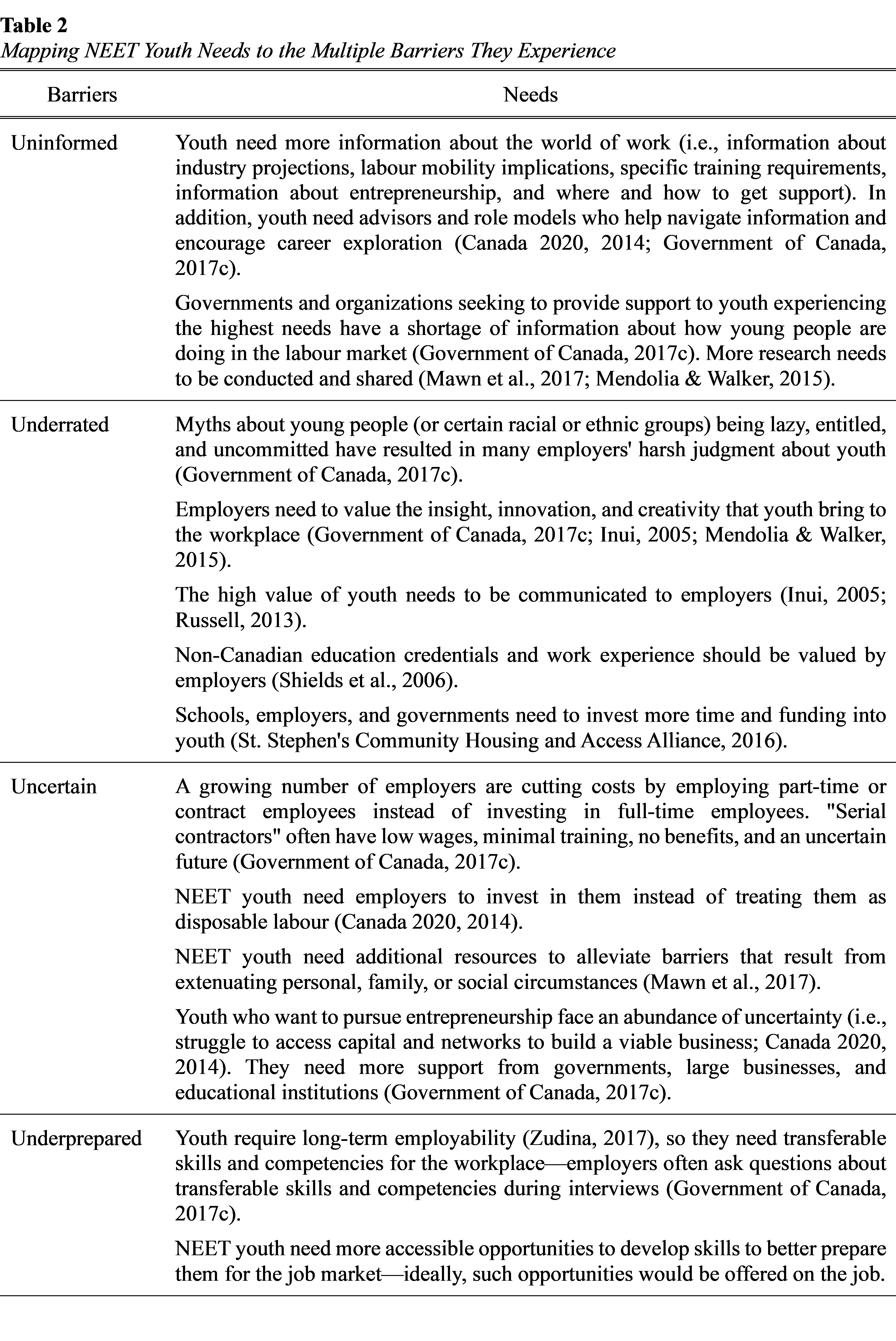

By identifying the driving factors that push youth towards NEET status, it becomes easier to pinpoint the multiple and complex needs of this heterogeneous group. The Government of Canada (2017c) commissioned a panel of experts in positive youth development from across the nation to write a report titled 13 Ways to Modernize Youth Employment in Canada: Strategies for a New World of Work. This Expert Panel on Youth Employment provided a robust list of barriers faced by youth when transitioning to employment (Expert Panel on Youth Employment, 2016). Categorization of barriers acknowledged shared responsibilities among stakeholders, communicated the needs of the youth, and pointed to some programmatic responses (see Table 2). We mapped these NEET barriers to their needs as identified in the relevant literature. The six categories of barriers to youth employment are as follows.

Preparing NEET Youths for the Workplace

There are three main areas that employment programs focus on to help NEET youth prepare for the workplace: employment skills development, career guidance, and job matching and placement. The role of each of these components is outlined in relation to the available research.

Employment Skills Development

The mismatch between young people’s qualifications, workplace requirements, and the labour market may be one of the most significant reasons for high youth unemployment (Choudhry et al., 2012; OECD, 2015; Skrzydlewska, 2013). The skills mismatch is mutually reinforcing: “young people without a strong skills foundation are more likely to drop out of school and face difficulties finding jobs while those who drop out and are jobless can hardly maintain and enhance their skills” (OECD, 2015, p. 22). The invisibility of pathways to the workplace in many countries and limited career education programs in high school (which could facilitate making connections between education and the workplace or labour market) are also cited as reasons for a skill mismatch (Bell & Benes, 2012). Educational systems may be failing to provide young people with the right skills for employment (Scarpetta et al., 2010; World Bank, 2010).

To support the effective navigation of the changing labour market, a variety of activities, support, and interventions are typically recommended for youth skills development (Dykeman et al., 2001), including work-related interventions (i.e., job shadowing and youth apprenticeships), advising interventions (i.e., career exploration and job-hunting preparation), introductory interventions (i.e., career field trips and career fairs), and curriculum-based interventions (i.e., career and job-related skills embedded in a curriculum). Authenticity of delivery is important for interventions that specifically seek to develop the transition to the workplace, with instructors playing a crucial role in providing knowledge about the world of work (Rehill et al., 2017).

Career Guidance

Research shows that most NEET youth wish to work and earn income (Dunn et al., 2014; Government of Canada, 2017c; Spielhofer et al., 2009), but they have varied motivations to take initiatives, such as job training or support seeking (Mawn et al., 2017; Shields et al., 2006). One of the challenges faced by NEET youth is the frequent misalignment of their career goals with those of their employers, and the work involved in addressing this misfit is complex and requires prolonged effort (Carlson et al., 2016). Youths would benefit from more guidance, advice, and information about options to make job selections based on greater information (Government of Canada, 2017c; Spielhofer et al., 2009).

Career goals may be helpful for placement but may not lead to sustainability. For instance, NEET youth may undergo interest inventories that catch a glimpse of their immediate interests but do not pertain to long-term goals. Once in employment, youth may disengage because of a lack of development or training on the part of the employer (Roberts, 2011). While most unemployed people desire to be employed (Dunn et al., 2014; Shildrick et al., 2012), answers to the question of under-employment and motivation to work remain elusive (Dunn et al., 2014). According to Worth (2005), some better NEET youth initiatives include employability assessments and employment counseling.

Job Matching and Placement

Matching NEET youth with jobs and ensuring their successful placement is a complex process. Understanding the complexities of the economic and political contexts of employment is challenging, “especially for at-risk youth who have a history of unsuccessful school experiences” (DeLuca et al., 2015, p. 191). Programs assisting youth with job matching offer various features, such as job contacts and networking, which NEET youth often lack. While job contacts have been efficient support for white-collar workers, evidence shows that they do not provide much help for NEET youths (Burleton et al., 2013). Job instability is higher in youth than in the general workforce, and the situation has worsened over the past decade (DeLuca et al., 2015; Marshall, 2012; OECD, 2006). Many service providers can connect NEET youth to employment; however, connecting youth to these services remains an issue (Carlson et al., 2016). Several youth employment programs acknowledge the importance of job-matching services that include job training, paid work placements, and work transition support. Other relevant supports that encourage job matching include internship programs, utilizing job-matching technologies, and striving for increased transparency in the job market (Carlson et al., 2016). Through a commitment to ongoing dialogue between employers (public and private sectors), employment services, youth, and the broader society, youth are more likely to find a job aligned with their individual needs (Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2015).

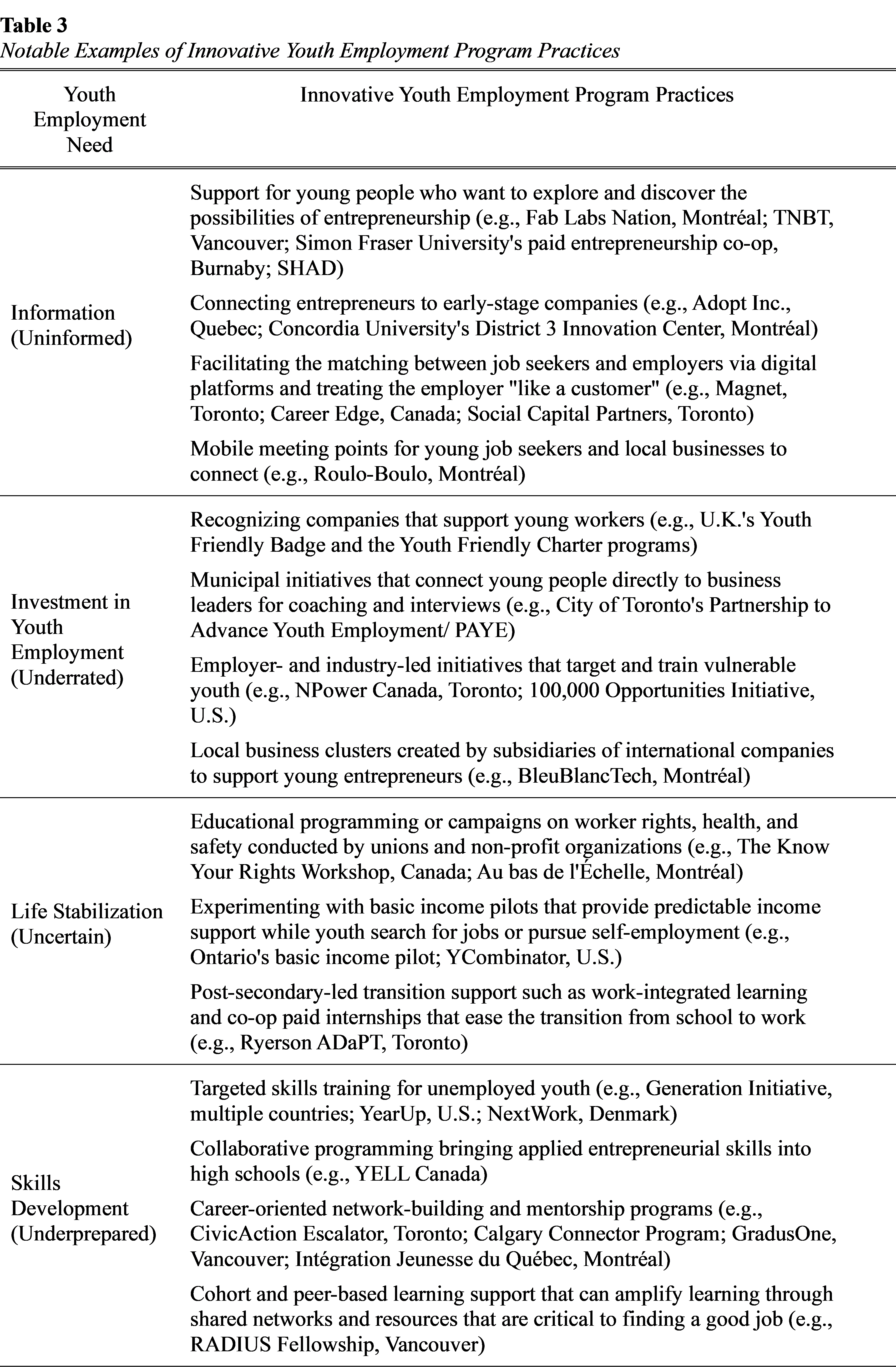

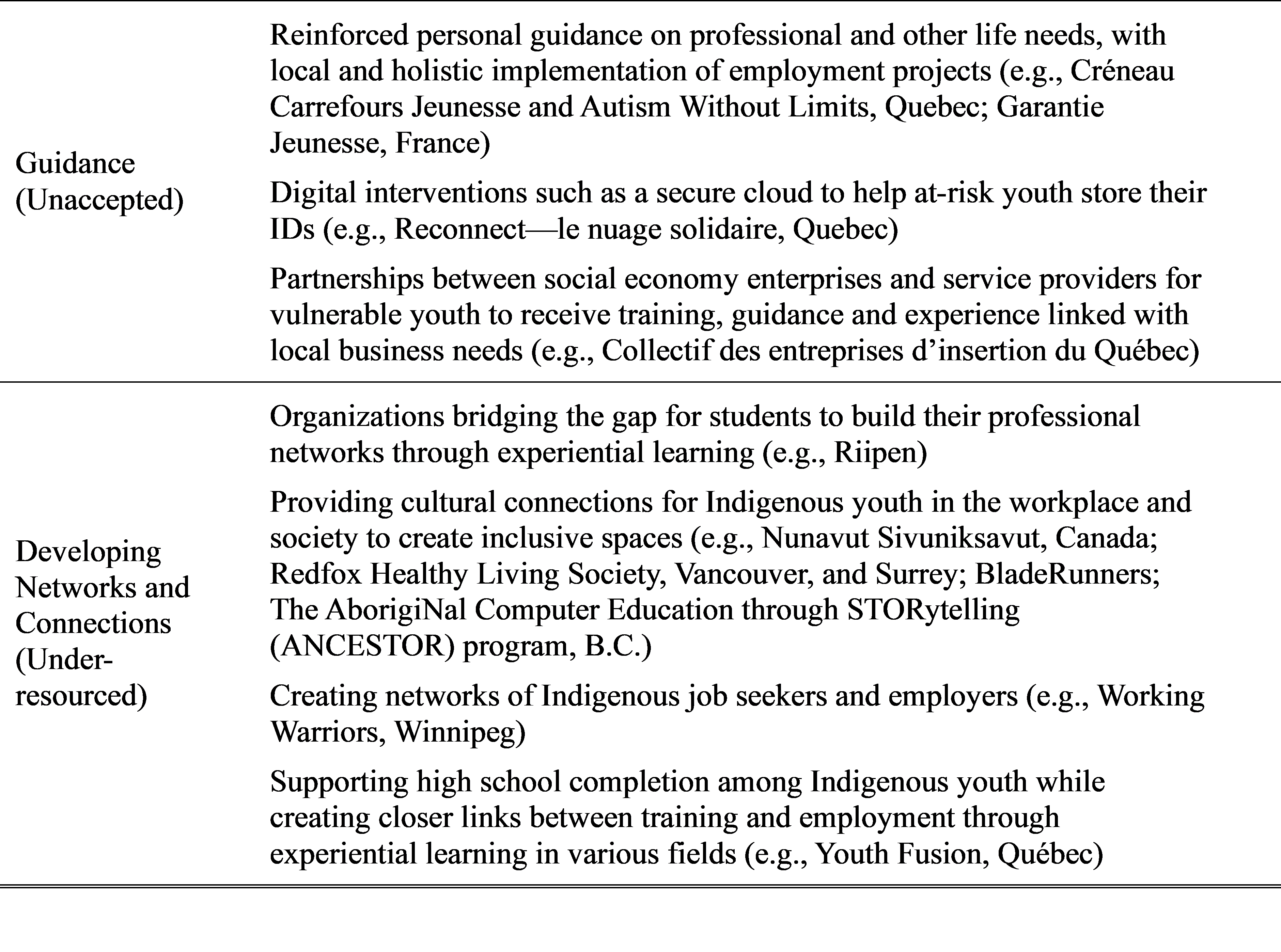

Promising Canadian Practices in NEET Youth Development

As part of its mission, the Government of Canada (2017c) examined the programs and support available across Canada to help young people in their quest for employment. Through an examination of focused programs led by employers, partnerships among the private sector, not-for-profit entities, and educational institutions, the Expert Panel identified several “notable examples of innovative practices” in youth employment programs in Canada and abroad. These practices (see Table 3) help overcome youth employment barriers through (a) information about career pathways (uninformed); (b) investment in youth employment (underrated); (c) life stabilization measures (uncertain); (d) skills development (under-prepared); (e) guidance (unaccepted); and (f) developing networks and connections (under-resourced).

To strengthen the provision of employment programs for youth, the Government of Canada (2016) recommends: (a) better coordination and stronger collaboration among sectors; (b) cohort and peer-based learning to strengthen learning and personal connections; (c) mentorship to help navigate the complexities of employment; (d) flexible and holistic programming to meet the complex needs of marginalized youth; and (e) exposing young people to options through opportunities such as experiential or project-based learning.

Discussion

Because Canadian youth face many barriers to obtaining and maintaining employment, supporting them in overcoming these challenges is a complex task. Youth employment programs help address the needs of NEET youth through employment skill development, career guidance, job matching, and placement. Given that NEET youth may have low educational attainment (Government of Canada, 2017c; Marshall, 2012; Mawn et al., 2017; Preston, 2008; Zudina, 2017) and become disengaged because of traditional schooling practices, it is important for employment skills training to be as hands-on and appealing as possible. Hands-on employment training may include experiential and project-based learning (Government of Canada, 2016). In addition, education systems should include employment skill development and offer direct workplace pathways for youths, such as apprenticeships and industry credentials, to set them up for success. More job pathways for youth would allow them to experiment with various options in low-risk environments (Government of Canada, 2016).

Career guidance is particularly important for NEET youth, who tend to lack support systems that provide this type of information (Foster, 2012; Mawn et al., 2017; Zudina, 2017). NEET youth need opportunities to explore their competencies and skills, and the careers for which they are best suited. In addition, NEET youth may need help with pathway planning if their career goals involve a multistep process. Valuable career guidance involves mentorship. Mentors can provide youth with guidance in navigating school-to-work transitions, finding their first job, accessing training support, making educational and career decisions, and dealing with other difficult life situations. While mentorship can be viewed as beneficial for all young people, it can be particularly important for multi-barriered youth: “youth who face additional challenges are often unwilling to engage in a system they believe that continues to fail them…having a knowledgeable mentor who can establish a relationship of trust with a young person through frequent contact over the long term is key to success” (Government of Canada, 2016, p. 16).

Job matching and placement are critical components of employment programs that target NEET youth, who may lack networks and connections that foster employment (Government of Canada, 2017c). Flexibility in job placement scheduling is essential for promoting the inclusion of vulnerable youths. For example, a young single parent with a baby can feel excluded from a Monday through Friday 9-5 job opportunity because of an inability to afford childcare for all five working days. A flexible and holistic youth employment program might adequately address the needs of this young single parent by coordinating with the employer to provide flexibility in the work schedule and negotiating a reduced cost of childcare at a daycare facility in the community. To promote the life stabilization of NEET youth transitioning into work placements, youth employment programs should provide stipends for pre-employment training, work clothing, technology, and transportation (MAESD, 2018).

Ultimately, a holistic approach to support young people in obtaining and maintaining employment is needed. For example, aspects such as building relationships, developing employability skills (e.g., CV writing), developing job skills and experience, addressing health and mental health concerns, and accessing transportation are elements that contribute to youths’ holistic ability to be successful in the workplace (McCreary Centre Society, 2014). Holistic support in employment programs helps vulnerable youth not only gain employment, but also develop the necessary skills, experience, and confidence needed to maintain and succeed within the workforce and life beyond.

Youth employment programs can overcome barriers experienced by NEET youth by addressing their need for information, investment, life stabilization, skills development, guidance, and the development of networks and connections. The more needs a youth employment program meets, the more comprehensive it becomes. Ideally, youth employment programs should target all six marginalized youth employment needs. Further research is needed on youth employment needs and their associated outcomes.

Finally, effective policies that support flexible and holistic youth employment programs require longitudinal, high-quality data that are largely unavailable. Collecting longitudinal data would provide a better understanding of NEET youth employment needs, barriers, and employment trends over time, allowing for more informed policymaking and programming for positive youth development.

In this review, we examined the literature on employment challenges of youth who may face multiple and complex barriers, and promising program practices developed to meet the employment needs of this population. By identifying a robust list of possible risk factors that are characteristic of NEET youth, we are better able to understand their needs in terms of the mentorship and support they require to become full participants in the labour market. Effective formal and informal kinds of mentorship in schools, homes, and employment services is perceived as one of the game-changers for youth who are trying to successfully transition to post-secondary education/training or the labour market. When thinking of the support required by NEET youth to propel them into secure employment, it is essential—although not a simple task—for us to approach the topic of support from a holistic perspective. Researchers are calling for all stakeholders (e.g., employers, policymakers, and service providers) in the field of youth employment development to place higher value on cross-sector (e.g., public and tertiary education, health, housing/community, governments, not-for-profit, private business, corporate, etc.) collaborations to better meet the complex needs of NEET youth and alleviate the employment barriers they face. Finally, given that there is a scarcity of quality research done in the field of NEET youth employment, we encourage colleagues to conduct research on the employment outcomes of NEET youth program interventions and strategies for re-engaging NEET in the labour market.

References

Bălan, M. (2014). Youth labor market vulnerabilities: Characteristics, dimensions and costs. Procedia Economics and Finance, 8, 66-72.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(14)00064-1

Bell, D., & Benes, K. (2012). Transitioning graduates to work: Improving the labour market success of poorly integrated new entrants (PINES) in Canada. Canadian Career Development Foundation.

Bell, N. F., & Blanchflower, D. G. (2011). Young people and the great recession. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 27(2), 241–267.

Bell, D., & Blanchflower, D. (2010). Young people and recession: A lost generation.

http://www.cepr.org/meets/wkcn/9/979/papers/Bell_%20Blanchflower.pdf.

Burleton, D., Gulati, S., McDonald, C., & Scarfone, S. (2013). Jobs in Canada: Where, what and for whom? TD Economics.

https://www.td.com/document/PDF/economics/special/JobsInCanada.pdf

CAMH & CMHA. (2010). Employment and education for people with mental illness. Discussion paper.

https://www.camh.ca/en/hospital/about_camh/influencing_public_policy/public_policy_submissions/employment_and_education/Documents/employment_discussion_paper_jan10.pdf

Canada 2020. (2014). Unemployed and underemployed youth: A challenge to Canada achieving its full economic potential. Paper series.

http://canada2020.ca/wpcontent/uploads/2014/11/2014_Canada2020_PaperSeries_EN_Issue-04_FINAL.pdf

Carlson, K., Crocker, J., & Pringle, C. (2016). Unlocking potential: Empowering our youth through employment.

https://trilliumhealthpartners.ca/newsroom/HCSC/Documents/HCSC_report_201605.pdf

Choudhry, M. T., Marelli, E., & Signorelli, M. (2012). Youth unemployment rate and impact of financial crisis. International Journal of Management, 33(1), 76–95.

https://doi.org/10.1108/01437721211212538

Crisp, R., & Powell, R. (2017). Young people and UK labour market policy: A critique of ’employability’ as a tool for understanding youth unemployment. Urban Studies, 54(8), 1784-1807. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016637567

DeLuca, C., Godden, L., Hutchinson, N. L., & Versnel, J. (2015). Preparing at-risk youth for a changing world: Revisiting a person-in-context model for transition to employment. Educational Research, 57(2), 182–200.

Dunn, A., Grasso, M. T., & Saunders, C. (2014). Unemployment and attitudes to work: Asking the ‘right’ question. Work, Employment & Society, 28(6), 904-925.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017014529008

Dykeman, C., Ingram, M., Wood, C., Charles, S., Chen, M., & Herr, E. L. (2001). The taxonomy of career development interventions that occur in America’s secondary schools. National Dissemination Centre for Career and Technical Education, The Ohio State University.

Expert Panel on Youth Employment. (2016). Understanding the realities: Youth employment in Canada (interim report).

https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/corporate/youth-expert-panel/interim-report.html

Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2015). Towards a better job matching for youth. Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH.

Foster, K. (2017). How can we understand the pitfalls of youth underemployment in Canada. CERIC.

http://contactpoint.ca/2017/10/how-can-we-understand-the-pitfalls-of-youth-underemployment-in-canada/

Foster, K. (2012). Youth employment and un(der) employment in Canada: More than a temporary problem? Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

http://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National%20Office/2012/10/ Youth%20Unemployment.pdf

Galarneau, D., Morissette, R., & Usalcas, J. (2013). What has changed for young people in Canada? Statistics Canada: Catalogue no. 75-006-X.

https://www.statcan.gc.ca/access_acces/alternative_alternatif.action?l=eng&loc=/pub/75-006-x/2013001/article/11847-eng.pdf

Gough, D., Oliver, S., & Thomas, J. (2012). An introduction to systematic reviews. Sage Publications.

Government of Canada. (2017a). Inclusion of marginalised people.

http://international.gc.ca/world-monde/issues_development- enjeux_developpement/human_rights-droits_homme/inclusion.aspx?lang=eng

Government of Canada. (2017b). Unlocking the potential of marginalised youth.

http://horizons.gc.ca/en/content/unlocking-potential- marginalised-youth

Government of Canada. (2017c). 13 ways to modernize youth employment in Canada. Strategies for a new world of work. Report from the Expert Panel on Youth Employment.

https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/corporate/youth-expert-panel/report-modern-strategies-youth-employment.html

Government of Canada. (2016). Understanding the realities: Youth employment in Canada. Interim report of the Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/corporate/youth-expert-panel/interim-report.html

Inui, A. (2005). Why Freeter and NEET are misunderstood: Recognizing the new precarious conditions of Japanese youth. Social Work and Society Online Journal, 3(2), 244–251. http://www.socwork.net/sws/article/view/200/260

John Howard Society of Ontario. (2014). Help wanted: Reducing barriers for Ontario’s youth with police records.

http://johnhoward.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/johnhoward-ontario-help-wanted.pdf

Lightman, N., & Gingrich, L. G. (2012). The intersection dynamics of social exclusion: Age, gender, race and immigrant status in Canada’s labour market. Canadian Ethnic Studies, 44(3), 121–145.

MacDonald, R. (2011). Youth transitions, unemployment and underemployment: Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose? Journal of Sociology, 47(4), 427–444.

MAESD. (2018). Youth Job Connection: Program Guidelines.

http://www.tcu.gov.on.ca/eng/eopg/publications/yjc_program_guidelines.pdf.

Marshall, K. (2012). Youth neither enrolled nor employed. Perspectives on Labour and Income, 24(2), 1–15.

Mawn, L., Oliver, E. J., Akhter, N., Bambra, C. L., Torgerson, C., Bridle, C., & Stain, H. J. (2017). Are we failing young people not in employment, education or training (NEETs)? A systematic review and meta-analysis of re-engagement interventions. Systematic Reviews, 6, 16–26.

McCreary Centre Society. (2014). Negotiating the barriers to employment for vulnerable youth in British Columbia.

http://www.cfeebc.org/research-innovation/youth-employment/study-vulnerable-youth/

McMurtry, R., & Curling, A. (2008). The review of the roots of youth violence, Volume 1: Findings, analysis, and conclusions. Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

Mendolia, S., & Walker, I. (2015). Youth unemployment and personality traits. IZA Journal of Labor Economics, 4(19). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40172-015-0035-3

Oreopoulos, P., Von Wachter, T., & Heisz, A. (2006). The short-and long-term career effects of graduating in a recession: Hysteresis and heterogeneity in the market for college graduates. National Bureau of Economic Research.

OECD. (2017). Education at A Glance 2017: OECD Indicators. OECD.

OECD. (2015). OECD skills outlook 2015: Youth, skills and employability.

http://www.keepeek.com/Digital-Asset-Management/oecd/education/oecd-skills-outlook-2015_9789264234178-en#.V9QaE7V0z8g#page24.

OECD. (2006). Starting well or losing their way? The position of youth in the labour market in OECD countries.

https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/starting-well-or-losing-their-way_351848125721

Preston, J. (2009). The urgency of postsecondary education for aboriginal peoples. Canadian Journal of Educational Administrative Policy, 86, 1–22.

https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/cjeap/article/view/42767/30627

Pullman, A., & Finnie, R. (2018). Skill and social inequality among Ontario’s NEET youth. Education Policy Research Initiative. Ontario Ministry of Children and Youth Services.

Rehill, J., Kashefpakdel, E. T., & Mann, A. (2017). Transition skills (mock interviews and CV workshops): What works? The Careers and Enterprise Company.

Roberts, S. (2011). Beyond ‘NEET’ and ‘tidy’ pathways: Considering the ‘missing middle’ of youth transition studies. Journal of Youth Studies, 14(1), 21–39.

Russell, L. (2013). Researching marginalised young people. Ethnography and Education, 8(1), 46–60.

Scarpetta, S., Sonnet, A., & Manfredi, T. (2010). Rising youth unemployment during the crisis: How to prevent negative long-term consequences for a generation. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Paper, No. 106. OECD.

Shields, J., Rahi, K., & Scholtz, A. (2006). Voices from the margins: Visible-minority immigrant and refugee youth experiences with employment exclusion in Toronto. CERIS Working Paper No. 47.

https://wall.oise.utoronto.ca/resources/Antonie_paper.pdf

Shildrick, T., MacDonald, R., Furlong, A., Roden, J., & Crow, R. (2012). Are ‘cultures of worklessness’ passed down the generations? Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

https://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/default/files/jrf/migrated/files/worklessness-families-employment-full.pdf

Skrzydlewska, J. K. (2013). Draft report on tackling youth unemployment: Possible ways out. Committee on Employment and Social Affairs, European Parliament.

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/EMPL-PR-508047_EN.pdf?redirect

Sonnet, A., Quintini, G., & Manfredi, T. (2010). Off to a good start? Jobs for youth. OECD.

Spielhofer, T., Benton, T., Evans, K., Featherstone, G., Golden, S., Nelson, J., & Smith, P. (2009). Increasing participation: Understanding young people who do not participate in education or training at 16 or 17. National Foundation for Educational Research.

https://lx.iriss.org.uk/sites/default/files/resources/Increasing%20participation.pdf

St. Stephen’s Community Housing and Access Alliance. (2016). Tired of the hustle: Youth voices on unemployment.

http://accessalliance.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/TiredoftheHustleReport.pdf

Standing, G. (2011). The precariat: The new dangerous class. Bloomsbury Academic.

Statistics Canada. (2015). Perspectives on the youth labour market in Canada, 1976 to 2015.

http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/161205/dq161205a-eng.htm

Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(45).

https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

Truth and Reconciliation Commission Canada. (2015). What we have learned: Principles of truth and reconciliation.

http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Findings/Principles of Truth and Reconciliation.pdf

Verick, S. (2009). Who is hit hardest during a financial crisis? The vulnerability of young men and women to unemployment in an economic downturn (Discussion paper No. 4359). IZA.

Versnel, J., DeLuca, C., Hutchinson, N. L., Hill, A., & Chin, P. (2011). International and national factors affecting school-to-work transition for at-risk youth in Canada: An integrative review. Canadian Journal of Career Development, 10(1), 21–31.

World Bank. (2010). School to work transition. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Worth, S. (2005). Beating the ‘churning’ trap in the youth labour market. Work, Employment & Society, 19(2), 403–414.

Zudina, A. (2017). What makes youth become NEET? The evidence from Russian LFS. Higher School of Economics Research Paper No. WP BRP 177/EC/2017.

https://ssrn.com/abstract=306